The following Appendix was originally intended to accompany the article “Building a Reproduction of the Downhill Harp” that was first published in the Bulletin of the Historical Harp Society, March 2010, but had not been completed in time to meet the Bulletin’s deadline. The author therefore takes this opportunity to publish it here on WireStrungHarp.com.

The cryptic verse carved into the side of the Downhill Harp has long held a fascination for those with an interest in the old Irish harps. For this reason I include a more detailed study of it.

The first record of this poem comes from George Sampson, who at the end of his account of the visit to Hampson relates that the following lines are “sculpted on the harp”:

In the time of Noah I was green,

After his flood I have not been seen,

Until seventeen hundred and two. I was found,

By Cormac Kelly under ground ;

He raised me up to that degree ;

Queen of Music they call me. [35]

However, this is not a fully accurate transcription of the true text found on the harp, as will be seen. Not only does Sampson seem to have misremembered some of the words, but it should also be noted that when he saw this inscription, parts of it were covered over with the metalwork previously referred to.

Unfortunately, many other subsequent and well-known reference sources have also failed to get this inscription correct. Bunting copies Sampson but mistakenly writes “days of Noah” instead of “time of Noah”.[36] Eugene O’Curry in turn repeats Bunting’s wording but uses “grown” instead of “green”.[37] Armstrong, working from a photograph, gets closer to the actual spelling, indicating in brackets those parts of the text that were obscured or unclear, but he also arbitrarily substitutes the word “Since” for Sampson’s “After”:

[In the] time of Noah I was green ;

[Since] his flood I have not been seen,

Until 17 hundred and 02 I was found

By C. R. Kely underground ;

[He raised me] up to that degree,

Queen of Musick [yo]u may ca[ll me]. [38]

Rensch takes her version of the text from Armstrong (though she spells “Kely” as Kelly).[39] Hayward reproduces a rather haphazard transcription:

In the time of Noah I was green,

Since his flood I had not been seen,

Until seventeen hundred and two I was found

By Cormac O Kelly underground :

He raised me up to that degree

That Queen of Musick you may call me.[40]

Rimmer’s text is surprisingly inaccurate: she merely takes Hayward’s wording but adorns it with her own invented alterations to the last line, altering a word at the beginning and giving a fanciful re-spelling of “Music” though it is perfectly clear on the original: “... The Queen of Musicke you may call me.” [41]

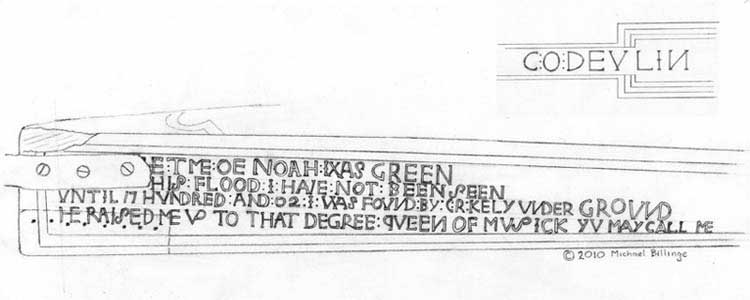

For clarification I have included the following line drawing made from a highly detailed photograph showing the actual carved letters as they can be seen on the harp. I have also indicated the extent of the copper plate which was partially covering the bottom line in Sampson’s and Armstrong’s time, but has since been removed.

FIGURE Y: A line drawing showing the actual carved letters as inscribed on the Downhill Harp.

(©2010 by Michael Billinge, used by permission.)

Please click on the image for a larger–sized image.

From a close study it is clear that Cormac began carving the verse by first producing a series of scribed construction lines parallel to the top edge of the soundbox, to act as a guide for his lettering (though the word “GROUND” clearly went beyond these and he is cramped for space for the last few words). Most of the letters have been carved with serifs and some of these have been ligated (joined into each other). These letters are clearly carved in the same style as the name “C:O:DEVLIN” on the forepillar. One curious observation is that in some cases the letter “N” has been mirror–reversed, with the diagonal line going in the wrong direction (this is also found in the “N” on the forepillar). Even stranger is the fact that this error becomes consistent halfway through the poem. Reading it through, up to and including the word “AND”, we see that all the letter “N”s are correctly carved, but after that they are all back-to-front. It is possible that Cormac was not over-familiar with writing or reading, but was merely copying shapes, for this anomaly seems unlikely otherwise.

Other curious things include what seems to be an earlier attempt at carving different letters (possibly “WA”) where the “N” and “O” of “NOAH” now appear; and at the end of the line, after the word “GREEN”, a faintly-scribed (but not carved) letter H can be detected. [I have not attempted to indicate these on the sketch].

There is also the question of what the actual words used at the start of the first two lines were. They are hidden from view by the iron strap (added some time after the harp was built to hold the neck into the soundbox) so they have not been visible since before Sampson made his observations. Therefore neither he nor Armstrong nor anyone else in over two hundred years has been able to read this part of the poem. The words may have been known to Hempson, who probably had the harp in his possession before the reinforcing strap was put on and had the verse read to him, and he could have repeated the words verbally to Sampson; but there is no way of determining for sure whether Sampson’s account is correct or not.

Observing the care Cormac took to align his text by scribing parallel guide lines, it can also be seen that, where visible, the beginning of each line is justified in a vertical alignment on the left side; thus it seems reasonable to assume that the other lines of text would also have started on the same alignment. However, even allowing for variations in letter-spacing, the choice of words given by Sampson does not account for the positioning of the text. The spacing strongly suggests that the words hidden beneath the strap should contain more letters than those given by Sampson. Although the word “AFTER” could just about be stretched out to fit the beginning of the second line, it is not possible to make the letters “IN” and “T” completely fill the gap for the first. This presents two options: either some other word was used to begin the poem or Cormac deliberately chose to start the poem with the first line indented. It is not easy to come up with an alternative wording that makes sense and also adequately fills the available space. Replacing the word “IN” with alternatives such as “FROM” or “BEFORE” (or “BEFOR”) may fill it better, but they do not fit the meaning so well. Therefore the indentation of the first line seems the most plausible option.

Unless the iron strap is removed it will not be possible to ascertain the correct version of the inscription, so we must make do with guesswork. A likely transcription would read as given below. I have used the letter “V” in place of “U” as Cormac did, but have not attempted to show the ligated text or reverse the letter “N”. I have also given Sampson’s “AFTER” rather than Armstrong’s “SINCE” because Armstrong was clearly guessing, whereas Sampson may have received his information directly from Hempson.

IN : THE : TME : OE NOAH : IWAS GREEN

AFTER : HIS : FLOOD : I : HAVE : NOT : BEEN SEEN

VNTIL 17 HVNDRED : AND : 02 : I : WAS FOVND : BY : C: R :KELY VNDER GROVND

HE RAISED ME VP TO THAT DEGREE : QVEEN OF MVSICK YV MAY CALL ME

The poem itself appears to be narrating something of the harp’s history, implying an antediluvian origin for the tree which then lay buried until resurrected by Cormac in 1702. Even allowing for 18th-century concepts of history, where many unexplained things were put down to the epoch-changing event of “The Flood”, the assumption has often been that Cormac was referring to a piece of ancient bog–wood which had lain undiscovered in the peat for millennia. Indeed, Armstrong may well have unquestioningly assumed this to be fact, for when writing of the poem he states:

“... inscription (which refers to the bog wood out of which it is constructed).” [42]

Notions have a habit of taking root, and today there still exists a commonly-held misconception that the old Irish harps’ soundboxes were made from ancient timber dug out of a bog. Yet none of the early accounts make any mention of this, and it seems more likely that the real origin of this belief is the interpretation of this poem made by writers in more recent times. If this is so, as it appears to be, then it becomes essential to try and understand the true significance and context of Cormac’s poem.

The first thing that should be noted is that Cormac’s verse is specific solely to this harp, and not other historical harps. Indeed, if the “ancient” harps were commonly made from timber that had grown before The Flood, there would have been no reason to hold this one up for specific comment. What is more, the favoured wood for the old Irish harps appears to be willow, which doesn’t survive too well as a “bog-wood”. So if we are to make true sense of this text we should forget about other instruments and concentrate on this one.

As has been shown, the Downhill harp was made not from willow but from European alder, and this timber has some specific properties that may help us interpret the poem. Alder shares certain qualities with willow, and this may have made Cormac consider it a suitable substitute. Like willow, it is light in weight and has a similar fibrous texture which resists splitting. It is also a little heavier and firmer in texture, so it takes carved detail better than willow does. However, it is unlikely that it was considered a superior wood for soundboxes in general, or surely more harps would have been made from it. Like willow, alder is often found growing in wetlands, by rivers and around lake shores; but unlike willow, alder wood is not prone to deterioration when submerged beneath the water table. Also, if dried out carefully, it will dry fairly uniformly, without too much twisting or distortion. This means that, with care, it was certainly possible to use alder which had been submerged as a viable source of timber for various carpentry tasks.

In 17th– and 18th–century Ireland, as natural–grown timber got more difficult to obtain and became an increasingly valuable commodity, woodworkers began to use old timber preserved in bogs where it was suitable for the task in hand. As such, a carpenter or tradesman (as we may assume Cormac was) would have been keen to obtain whatever good timber he could, as and when it became available. Thus he would be resourcing and preparing his raw material from a variety of sources, including both felled and excavated timber. In the case of alder, digging timber out of the ground may not have been confined to the areas of peat-bog alone. Water–logged ground along the margins of lake shores, where alder carrs were to be found, would also have been a likely source for fallen trunks and branches.

At one time in the highlands of Scotland, where it was used for making furniture, alder acquired the nickname of “Scottish Mahogany” [see Note 20] from the reddish colour that it can turn after it has been cut, and it is believed that makers devised various ways to enhance this colouring. One method could have been to submerge the timber in a peat bog, as the effect of the peat is known to darken the timber. However, prolonged submergence would result in it turning “as black as ebony”. (This is thought to be due to the tannin, of which alder has a high content, reacting to the peat. It is interesting to note that the colour of ancient “bog–oak” is also black, and oak is likewise noted for its high tannin content). Another possible reason why alder may have been deliberately put into a peat bog is that it was thought that submerging the timber in a mixture of peat and lime would help increase the wood’s resistance to woodworm attack, alder having acquired a reputation for being one of the woodworm’s favoured timbers.

The above presents us with two plausible interpretations for the poem. The first is that the harp was indeed made from a piece of alder which had been salvaged from water–logged ground (peat bog or otherwise); and the second that Cormac deliberately put the timber into a bog himself, as a treatment to either enhance the colour or increase its resistance to woodworm. However, either way it is unlikely that the timber had lain submerged for any great period of time or else it would have been much darker in colour. [N.B. Although today the harp looks fairly dark in colour, this is the result of later finishes, especially that applied in 1963. The original colour was far lighter].

It is possible that in this little verse Cormac may have taken the threads of truth and, expanding the story a little, spun them into a “yarn”. But, whatever the real truth of the matter, this poem is specific to the Downhill harp alone, and I am not aware of any evidence, either physical, scientific or historical, which supports the belief that any of the existing harps were made from “ancient wood dug out of a bog”. Indeed, the very fact that Cormac is making such a feature of this tends to suggest that what he did with the Downhill was a highly unusual, if not unique, occurrence.

© 2011 Michael Billinge

[35] Sampson’s letter (op.cit.), p. 84.

[36] Bunting, 1840 (op.cit.), p. 76.

[37] Eugene O’Curry, On the Manners and Customs of The Ancient Irish, Vol. III, 1873 (published posthumously), p. 294. N.B. O’Curry gives the source of the information as a letter from George Petrie, who may in turn have taken this from Bunting.

[38] Armstrong (op.cit.), p. 88.

[39]

Roslyn Rensch, The Harp, 1969, p. 93.

Roslyn Rensch, Harps & Harpists, 1989, p. 125.

[40] Richard Hayward, The Story of The Irish Harp, 1954, p. 21.

[41] Joan Rimmer, The Irish Harp, 1969, p. 76.

[42] Armstrong (op.cit.), p. 88.

© 2011 Michael Billinge

Except where otherwise noted, content on this site is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available by contacting us at editor@wirestrungharp.com.