Tigh nan Teud or, as usually translated House of the Harp string, is also claimed to be the centre of Scotland, probably due to its inclusion in a verse of a Gaelic poem where it is mentioned apparently in connection with a fifteenth century Clan Donald Chieftain. When examined against the surviving contemporary archives the evidence found there presents a somewhat different picture.

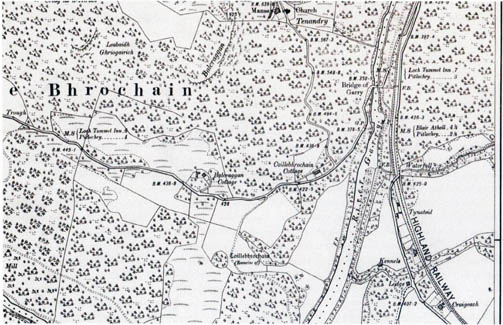

Ordnance Survey Map displaying the Gaelic place name represented phonetically as Tynateid.

Tigh nan Teud or House of strings

is about two miles north of Pitlochry and just before the Southern entrance to the Pass of Killiecrankie. It is an example of the Ordnance Survey Map Maker’s inability to cope with Gaelic place names and now appears on the maps as Tigh–na–Geat

. From the original nineteenth century maps through to and including the revised edition of 1974 it appears spelt phonetically as Tynateid

, but sometime between then and 1979 the change to the current spelling occurred. This might reflect a somewhat belated response to Tynageat

a local variant which can be traced from 1873 which has carried over into modern general usage. Further confusion is added when the usual translation of both interprets it to mean the House of the harp string

, with the addition then of the story that it was so named because it was the house of a ferryman who mended a harp string for Mary Queen of Scots when she passed through on route to Blair Castle.[1]

A somewhat more solid traditional reference can be found in a Gaelic poem which contains the lines;—

Domhnall Ballach nan Garbh Chrioch

Rinn Tigh nan Teud aig leth Alba ’na chrich [2]

Domhnall Ballach of the Rough Bounds

who made a boundary of the House of the Harp–strings,

at the half–way point of Scotland.[3]

This is a common motif in poems associated with the Clan Donald, although normally less specific than this regarding the actual place usually limiting it to just a non specific house

(taigh is leth Alba)[4] or a township

, (Baile agus leth Alban)[5]. It has been pointed out that the site does not lay within the confines of the original Lordship of the Isles and has therefore been interpreted to mean that Gaels represented by Clan Donald would share Alba

with the Gall provided their right to the whole is acknowledged.[6]

It was probably as a result of this claim that locally Tigh nan Teud

is stated to be at the geographical centre of Scotland, although such concepts are elastic and depend upon where the measurements are being made from and not surprisingly there are several other places which make a similar claims. Domhnall Ballach who was mentioned in the poem quoted above died in 1476, but the poem is a much later composition and the introduction of the place name has a very tenuous connection with the earlier motifs.[7]

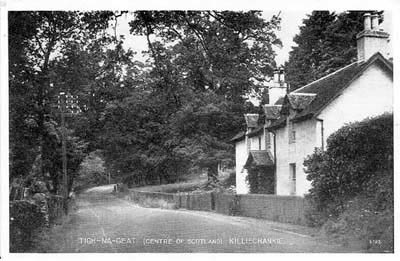

Currently Tigh nan Teud/Tigh–na–Geat is a category C listed building, described by Historic Scotland as an Early 19th century, 2– storey 3–bay rectangular plan traditional harled house with rustic porch, possibly incorporating some earlier fabric, along with two rectangular plan ancillary buildings to the east and north

. As it stands today it has undergone some extension to the rear but the basic dwelling is still easily recognisable as that shown in a number of early twentieth century pictures (with the development of Pitlochry as a Victorian resort it was a popular subject for postcards).

Postcard of Tigh-na-Geat looking north towards Killiecrankie. To see the postcard full-size, please click on the above image.

It is clear though from those pictures that the alignment and grading of the road in front of the house has changed between then and now, along with the removal of quite a number of mature trees. Exploring the original topography is further complicated by the presence of the railway line, built in 1863; which although not visible from the road runs parallel to it, just behind the buildings and beyond that is the modern dual carriageway A9 trunk road. Prior to the appearance of Tynateid

on the Ordnance Survey series of maps, earlier maps only had a township called Bailephuirt marked roughly in the same area.

However, Tigh nan Teud and Bailephuirt were not the same place, the latter translated in some of the guidebooks as Ferrytown

(presumably from a more literal township of the port

). Bailephuirt was or had become part of the Atholl Estate[8] while Tigh nan Teud was within the lands of the Robertson’s of Fascallie who in turn were a major branch of the Robertson’s of Struan. The Fascallie estate included both Fascallie itself which mostly lay to the north side of the Pass of Killiecrankie marked today by Old Fascallie House, and the lands of Dysart at the southern end of the pass which included Tigh nan Teud. It seems clear from the contemporary records that both places were quite close together with Tigh nan Teud being nearest to the river, in which case any chance of locating any residual remains of Bailephuirt have probably been obliterated by the construction of the railway line.

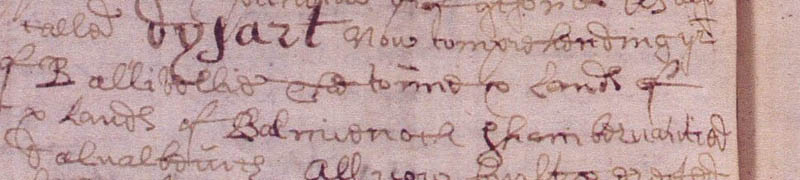

Turning to the contemporary records presents an interesting picture as it would seem that Tigh nan Teud was not the original form of the name, something which gives a twist to the question of how old the poem quoted earlier with its reference to Domhnall Ballach actually was. The earliest document so far located in which a version of the name appears is a record of a Fascally Deed of February 1679 which has been entered in the Books of Council and Session where, under Dysart, the name is recorded as Shambernantied

.[9] A similar version of that name then appears in a Rental of the Barony of Faskwlie

[Fascallie] with a list of debts owing to Faskwlie for 1688.[10] Under the section covering Dysart is listed a Chamernantead

which payed a cash rental of £26–13–4 Scots along with further payments made in kind

which included a quart of aquavity

, a Crew lamb

and 3 pultry

.

The Fascally Deed of February 1679

Image courtesy of the National Records of Scotland, RD4/44 page 506.

In a list of Fascallie’s tenants in 1700 there is what appears to be a correct Gaelic version of the name, but unfortunately it is one of a number of documents bound into one volume and the items are attached to tabs which in this case overlaps the edge of the list by some 5 mm thereby covering the first few letters of the names of the townships. Allowing for the hidden letters the name in this instance was probably Seòmar nan teid

.[11] The tenants at that point were a Colin Ross younger and Walter Ross his son, but close by among the tenants at Ballintuim was a John Robertson alias Clarsair.

As Chamber or Chalmernateid

the name can be followed from 1691 in the Fascallie Baron Court Book right down until 1717 when Tighnateid

makes its first appearance. From that point on in the Fascallie papers both names are used interchangeably until around 1733 when Tighnateid takes over completely. It is also interesting to follow some of the tenants over that same period. In 1704 a Colin Ross in Chalmernateid was ordered by the Barony Court to pay three years back rents owed to Fascally and later the same year described as Colin Ross in Ballefourt

sometime in Chalmernateid he was being pursued by Alex Robertson of Fascally for £10 Scots for the comprising of the biggings of Chalmernateid

.[12]

By 1707 the tenant of Chalmernateid was a John Robertson alias Clarsair [13] but his time there was short lived and in a list of money owing to Fascally in 1716, the then tenant a Malcolm Stewart owed Fascally two years rent while John Clarsair sometyme in Chalmernateid now in Ballefourt

still owed Fascally £28-15sh.[14] However not too much should should be made of this connection between a clarsair

and the placename. When in 1718 there was an inquisition held to determine the march (boundary) between Atholl’s lands and those of Fascally one of the witnesses described as Alexander Menzies Boatman at Garie

had formerly lived at Ballefuirt

and was probably the same man who subsequently became the tenant of Tighnateid in 1727 and therefore provides a possible link to a Ferry connection.[15]

Although the relatively modern version of the place name Tigh nan Teid with its translation as House of strings

, with the strings understood to be those of a harp cannot be totally ruled out; there are several problems with that interpretation. Baile

was the normal prefix to a placename comprising a small clustered farmtown

. The use of Tigh

meaning an individual building was far less common while the original form of this placename of Chalmer/Chamber

(or Seòmar) meaning a specific room appears to be unique in the context of a placename. It is also notable that in the earlier forms, whether using Chalmer

or Tigh

in various phonetical spellings, they are nearly always joined by na

and not nan

, indicating the name has undergone some modern regularisation.

If therefore an alternative origin for the name is explored then a connection between ropes and boats enters the field. The nearby farmtown of Balephuirt

was certainly translated in one early guidebook to Pitlochry as Ferrytown

, and a ferry of some sort operated across the Garry at some point across that stretch of the river where it had broadened out after leaving the rocky gorge forming the Pass of Killiecrankie. The impetus to build the bridge over the Garry (click to see the photograph The Old Bridge of Garry on the British Library website) was prompted by an accident in 1767 when it was reported that twenty seven people lost their lives returning from visiting the Moulin market when the ferryboat carrying thirty people was carried away by the current and over turned.[16]

Any remaining trace of Balephuirt was probably removed by the engineering works for the railway line but it would seem to have been on the slope just a few hundred yards above the river and in turn an equal distance downstream from where the river leaves the south end of the gorge, which would have allowed the flow of water a chance to slow. Assuming that the current building at Tigh na Teid is still on the original position of Chalmernanteud

then it would have been between Balephuirt and the river and in the right area to have been the room

or store where the boat’s ropes were kept or even perhaps were being made. Which in turn raises the question regarding what sort of ferry it was. There seems to have been little work published on the many small ferries which worked on highland rivers before they were eventually bridged. Probably because, from a having some familiarity with the records in which such information might be found, it is noticeable that they are rarely mentioned or described in any useful way.

However two of the items in the payment in kind part of the 1688 rental for Chalmernantead do stand out. The annual payment of one Crew Lamb

, is a form encountered before. There were similar payments for half a Crew Wedder

in the early 18th century rentals for the piper John MacIntyre at his holding of Kinaclacher at Loch Rannoch and what the Crew

part meant was resolved when it was realised that it was to provide food for the crew of the boat Menzies of Weem kept for use on the loch. Although all the rentals under Dysart

included crew lambs

the second of the two items which catch the eye was the quart of acquavity

which only featured at Chalmernantead; suggesting perhaps that it was actually distilled there for sale to waiting ferry passengers (although there is no indication there was ever a hostelry or changehouse there).

While it seems clear that there was a ferry across the Garry around that point it still does not explain why it is only that particular ferry which has so far left a placename relating to the vessels ropes? As the boat is not likely to have had a sail the only rope needed would have been for mooring when it reached the side of the river. Unless that is it was a raft type of vessel drawn across river by rope. Certainly something of that sort would have been more likely to have held the thirty passengers known to have been on board with their belongings at the time of the accident which led to the bridge being built. Such a system would have needed a lot of ropes and somewhere for their repair and storage.

There is at least one precedent for such a ferry elsewhere in an engraving of Kelso and the River Tweed in Slezer’s Theatrum Scotiae of 1693. Viewed from the south side of the river looking towards Kelso on the other bank, it shows in the foreground a large rectangular raft type of vessel with a mounted horseman and pack horse with its leader on board while another horse and rider seems about to join them. There also appears to be a similar sort of craft close to the point on the opposite riverbank where the road up to the town starts.

The only visible sign of a method of propulsion is at the shore side of the raft where a figure with a pole is pushing into the riverbank but he is more likely to be about to help push of from the shore once the second rider has boarded. Even with the river at its lowest flows the idea that it could be crossed by punting that sort of craft over with a pole seems very unlikely. Especially as the River Tweed like its northern counterpart the Spey was known as a notoriously difficult river to cross.[17]

John Slezer's Engraving of Kelso and the River Tweed, 1693 (image courtesy of NLS licence for non-commercial use)

Although there are no signs of any ropes in the picture, the engraving only tends to concentrate on the main features; so any rope across the river or to an oared boat sitting about mid–river directly in line with the ferry route may have not been included by the artist. It is therefore very likely that some form of propulsion system

involving ropes was employed.[18]

The most recent modern placename of Tigh–na–Geat

is clearly wrong, though the change to Geat

may have been due to a local miss–understanding of the Gaelic word Teud

and a belief that the house was at the Gate–way

to the Pass of Killiecrankie. It also seems clear that the earliest form of the name used variations of the word Chamber

therefore the Gaelic poem which includes the line Tigh nan Teud must be later than that forms first appearance in 1717.

The interpretation of the last part of the place name as the Gaelic word teud

meaning string or rope seems sound, but the exact nature of the string is less certain. In poetic use teud

has certainly become closely associated with musical instrument strings, but its use here especially with the older form of the placename using Chamber

; along with the close by township of Ballephuirt

suggests a somewhat more practical use for the string. The proximity of the ferry leaves little doubt that the Port

in the township name is connected to that rather than Port in a musical sense.

Port

was used for any point where a boat landing could be made and the corresponding ferry across the River Tummel a few miles further south near Fonab was called Port na Craig

. The vessel was able to carry horses and carts but, due to the river being fairly rapid it was found to be impossible to use an ordinary boat with oars and so a ferryboat

was constructed that was fastened by a chain to a rock in the centre of the river and by angling the bow of the boat slightly to one side in the current it was diverted across the stream rather like a pendulum.[19]

It is the use of the word Chamber

in the original placename which raises the most questions. Chamber or Chalmer are Scots not Gaelic which therefore makes the whole place–name something of a hybrid. Presumably it initially denoted a small single room building between the township of Ballephuirt and the actual ferry. But following the settlement of the dispute regarding the march between Fascally’s lands and the Duke of Atholl’s lands of Ballephuirt in 1718, additional buildings at Chamber nan Teud was the reason for the change from Chamber

to Tigh

.[20] Certainly the ferry was and remained Fascally’s according to correspondence among the Atholl papers relating to the first attempt to provide a bridge in 1738; which described the tenants as being too poor to make much of a contribution to its cost and from men who may not use the bridge once in 7 years, a ferry boat of Faskallie’s being more convenient.

[21]

Likewise the rise to prominence of Tighnanteud on the most recent maps and the decline of Ballephuirt can be seen as the result of changing circumstances. Although following the building of the bridge in 1770 both places would have lost their main function, Ballephuirt being a small township lingered as a name on the maps into the first half of the nineteenth century. However, it seems to have disappeared following the land scape work for the railway in 1863, while the building at Tighnanteud which still remained standing took its place on the maps when the first Ordnance Survey was undertaken.[22]

Finally there is the question of the traditional tale. This in its fullest version involves Mary Queen of Scots on her way to visit the Earl of Atholl, pausing for a rest and the Queen calling for her harp only to find some strings are broken. They then move on to the Ferrymans house where he arranges for an old harper who lives in the neighbourhood to replace the strings. From that point the ferryman’s house which was known as Balnafuirt had ever since been named Tyn–Geat, or the house of the harp–string.[23]

It is difficult to know how old this story

is but there are some clues. The claim that Queen Mary played the harp was mainly the work of John Gunn in his report on the two Lude harps for the Highland Society of Scotland published in 1807. The real connection between the Queen and the harp named after her can be found here on this site’s in–depth page on the Queen Mary Harp. What is probably significant is that Gunn actually makes no reference to this episode or the placename suggesting the tale

was a later concoction. Indeed the way in which the disappearance of Balnafuirt and the substitution of Tyn–Geat is accounted for suggests it was some time after the railway had come and the version of the name which used Geat

had started to become a local usage. Coincidentally coinciding with the rise of Pitlochry as a tourist centre.

There are two major problems with this story. Firstly when Queen Mary made her trip to Blair Castle in August 1564 she did not take that route but used the Shinagag Road which ran from Kirkmichael to Old Blair rather than coming up from the south past Tigh nan Teid and then through the Pass of Killicrankie.[24] Secondly there is no evidence that Queen Mary ever played the harp, let alone a metal strung clarsach. Brought up at the French Court her musical tastes were formed there and the fashionable instruments at that time were the lute and virginals, mainly used to accompany the voice.

These were also the only instruments she was described as using after her return to Scotland, and both there and previously while she was in France she was the subject of the most intensive scrutiny by the agents of her fellow monarch Elizabeth of England. An inquisitiveness by one woman of another which went beyond the purely political aspects of Mary’s life. Indeed from the very diplomatic relies given to Queen Elizabeth’s questions by her agents there seems little doubt that if Queen Mary had shown any sign of lowering her courtly

standards by using an indigenous Scottish harp, Elizabeth would have been told. Even native Scottish Gaels like the Earl of Argyll when in communication with the English crown treated their own culture with a degree of subservience.[25]

Apart from the English accounts, the evidence from the Scottish Records does not make any case for the harp being one of Queen Mary’s accomplishments. There are no signs of harps actually at court during her reign, although as was common when she was travelling disbursements were made to lots of musicians which did include harpers and pipers, from both highland and lowland backgrounds. It would also seem from the evidence of her Household Accounts that her own instruments, the lutes and a virginal were transported separately from her and sometimes from each other at times being taken directly to the end destinations rather than just to the intermittent stops on her journey.[26]

[1] MacKay L, The Atholl Illustrated Tourist Guide to Pitlochry (circa 1912) p 35–36

[2] Quoted in an article called Some Knotty Points in British Ethnology

by Mr Alexander MacDonald, Chief Accountant of the Highland Railway, in Inverness Scientific Society and Field Club Transactions volume 7 (1912) page 306

[3] Translation from MacInnes John, Gaelic Poetry and Historical Tradition in The Middle Ages in the Highlands. Inverness Field Club. (1981), page 154

[4] MacKenzie Annie, ed. Orain Iain Luim, (1973). P 148, line 1843

[5] Watson William, Bardachd Ghaidhlig, (1976). Page 282

[6] MacInnes John, Gaelic Poetry and Historical Tradition in The Middle Ages in the Highlands. Inverness Field Club, (1981). Page 154

[7] My thanks to Colm O’Boyle for identifying the original source of the verse as coming from a lament on a chief of Glengarry first published in Dain agus Orain by Archibald Grant (b. 1785 – p. 1863), 1863 page 94

[8] National Library of Scotland (NLS), Fascally Papers, MS 1433 f. 136, Regarding Atholls lands of Ballefurt and Fascalie’s March in 1718 it noted that Atholl had purchased the lands of Ballefurt from a William Robertson.

[9] NRS RD4/44 pp 505-507

[10] National Records of Scotland (NRS), GD 111/3/29

[11] NLS MS 1443 f. 24; This method of record storing is apparently known as a guard and file book

.

[12] NLS MS 1443 f.44

[13] NLS MS 1433 f, when a complaint was made by his wife Elspeth Robertson against two other women that they did with no offence offered strike her causing a great quantitie of blood at my mouth and nose

.

[14] NLS MS 1439 f.9

[15] NLS MS 1433 f. 136; MS 1446 f. 71

[16] Lloyd’s Evening Post. 4 March 1767

[17] Stell, Geoffrey. By Land and Sea in Medieval and Early Modern Scotland. In ROSC–Review of Scottish Culture. Number 4. (1988) p 31 and plate 2.

[18] The raft

is holding square onto the river bank with most of its length pointing out towards mid stream. A dificult position to hold with just one man and a pole on the wrong side

at the riverbank end, unless the raft was being held also using ropes.

[19] Taylor D. ed. The Counties of Perth and Kinross- The Third Statistical Account of Scotland. (1979), p 202

[20] NLS MS 1433

[21] Atholl Estate Papers. NRAS234/Box 46/12/9

[22] My thanks to Dr Kirsteen Mulhern, Maps and Plans Archivist. National Records of Scotland, for searching the relevant sections of the 1861–4 Perth and Inverness Junction Railway plans for any remaining trace of Ballephuirt.

[23] MacKay L, The Atholl Illustrated Tourist Guide to Pitlochry. (circa 1912), pp 35–36

[24] Kerr John, Old Roads to Strathardle, Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness volume LI (re–print 1984) pp 9 and 48

[25] Bain, Joseph. Ed. Calendar of the State Papers Relating to Scotland and Mary Queen of Scots, 1547 – 1603, (1898), p 469 In August 1560 Argyll had received an ambassador from O’Neill

carrying a letter which he sent with a translation to Elizabeth’s Court so that they could see the strayngenes of their ortographie

. Argyll also reported that O’Neill’s ambassador had arrived half naked having had to exchange his safron shirt on route for food.

[26] NRS E33/8 f. 21r. These personal Household Accounts were kept in French. My thanks to Thomas Brochard for the translations.

Submitted by Keith Sanger, 13 November, 2015

Except where otherwise noted, content on this site is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available by contacting us at editor@wirestrungharp.com.