The harper, Patrick Byrne occupies a fairly unique position among the last of the professional players of the Irish harp. As a pupil of Edward McBride, who was in turn a pupil of Arthur O’Neill, Patrick was heir to albeit a declining, but unbroken tradition, yet at the same time, during his lifespan he seems to have been the most successful among his compatriots in adapting to his changing world. He appears to have maintained a comfortable living, possibly more so than his immediate predecessors, and the source material relating to him certainly enables his biography to be substantially more complete than any of the other harpers be they contemporaries or earlier. Yet, despite this relative wealth of material there is still one important gap in his life prior to him being recorded as a pupil at the second Irish Harp Society school in 1821.

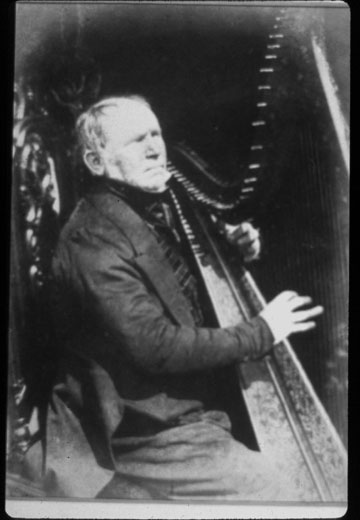

photograph of Patrick Byrne by Hill and Adamson, Edinburgh

Patrick Byrne was probably born in the parish of Magheracloone, in what by that time was part of the Shirley owned estate of Farney in County Monaghan. His father was a Thomas Byrne and according to the inscription on his tombstone in St Peters burial ground, which was erected by Patrick, described as the eldest son, his father ‘Thomas Byrne died at Greaghlone on the 20th December 1843 aged 74 years. He was born and reared on the said Townland of Greaghlone part of which has been occupied by his Family upwards of 200 years’.[1] This last is consistent with the claim that the ‘Pierce O’Beirne from Greaghlone who was a captain in the army during the rising of 1641, and took a very active part in wresting the country from the planter’s grip, was the great–great–great–great–grandfather of the Harper Byrne who became a Protestant and whose tomb is in the ‘Bullys’ ‘Acre’(Carrickmacross)’.[2] His forbears revolutionary activities seem not to have severed their connection with that area and another link in the pedigree is probably the Patrick O’Birne who was one of the tenants at Greaghlone in the 1663 and 1665 Hearth Tax Rolls.

Patrick the Harper first comes into view in a report to the Irish Harp Society annual meeting of the 20th August 1821, when Edward McBride, the then tutor, reported that there were four resident pupils, one of whom was a ‘Patrick Byrne (blind), county Meath and aged 23 years’.[3] A short statement which manages to include at least one if not two errors, albeit that the geographical one was partially corrected in the letter of recommendation supplied to Patrick on the completion of his training. The Byrne family home was in that part of Monaghan which is close to the point where it comes together with counties Louth, Cavan and Meath. Greaghlone itself is almost on the border between Monaghan and Cavan and is almost equidistant from the two nearest urban centres of Carrickmacross and across the border, Kingscourt in county Cavan, both places with which he has at various times been associated, for example, in his letter of recommendation from the Harp Society which he received on the 14th May 1822, he was therein described as being from Kingscourt, but an additional line has been squeezed in that reads, ‘and a native of the Barony of Farney in the County Monaghan’. It also stated that he had been admitted to the school on 21 February 1820, and contains, apart from the signatures of the Harp Society committee, that of Valentine Rainey, indicating that he must have benefited from the tuition of two of Arthur O’Neill’s pupils.[4]

The second possible error in McBride’s report was the question of Patrick’s age. If he was 23 at the time then it means that he would have been born around 1798, but according to the age given on his grave stone which was erected by his patron, Evelyn Shirley of Lough Fea who as his executor, was in close contact with Patrick’s surviving relatives and therefore should be accurate, he was born four years earlier in 1794 and this would have made him around 27 years old when he commenced his training. Either age would have been rather late to start as a professional musician, yet according to McBride’s progress report to the Society Patrick had already acquired 60 tunes, more than any of the other students and certainly the contemporary reports of his playing suggest that he was a competent musician. All of which makes it highly likely that he had some previous musical experience before entering the harp school, but unfortunately, this is the period of his life about which there is still little known.

Once Patrick had left the school in 1822, the next period of his life can be reasonably well established from the surviving circumstantial evidence. He would have initially returned to his home in Greaghlone, in Farney and the Shirley family who owned the barony are the key to his future progress. The Shirley home at Lough Fea would have been a social centre for as it was at the time quaintly phrased, ‘the quality’ of the local Carrickmacross area, his future source of patronage on his home ground. The main Shirley estate was however, in England, at Ettington, in Warwickshire, not far from Stratford upon Avon and the Shakespeare medal that Patrick was given by the Shakespeare Club, according to his will, in 1829 points firmly to the direction he took under the Shirley patronage. He is also known to have performed at Leamington Spa and at Staunton Harold Hall, the home of another branch of the Shirley family (the Earls Ferrer) near Ashby–de–la Zouch in Derbyshire and another of their houses, Chartley Castle near Stafford. There is a single sheet of undated crested note paper with the remains of a wax seal and signed by Earl Ferrers at Chartley, among Patrick’s papers, which reads ‘The bearer of this Patrick Byrne is the celerbrated ‘Irish Harper’ and private harper to me’.[5]

These patrons would have placed him right in the centre of the landed English society, most of whom, like the Shirley’s themselves also maintained homes closer to and were part of the London Social circles and this would have brought Patrick to the notice of the peak of London Society and in 1841 he was appointed Irish Harper to HRH Prince Albert. This does not appear to have been just a token position since the Ballina Chronicle in September 1849 reported that ‘Mr Patrick Byrne the Irish Harper from Dublin, performs every evening on the national instrument before the Loyal party at Balmoral’. While performing at Balmoral, Patrick would have come into contact with another representative of a Gaelic musical art form in the process of adapting to a changing world, the Queens highland piper, Angus MacKay.[6]

This was not the first time that the harper had been to Scotland, the Edinburgh Advertiser of the 19th December 1837 carried a long account of his performances, and again on the 16th of January 1838 a shorter account reporting that he was about to take his leave of the city. Both accounts emphasize that he only performed to private parties, the earlier report firmly stating that;–

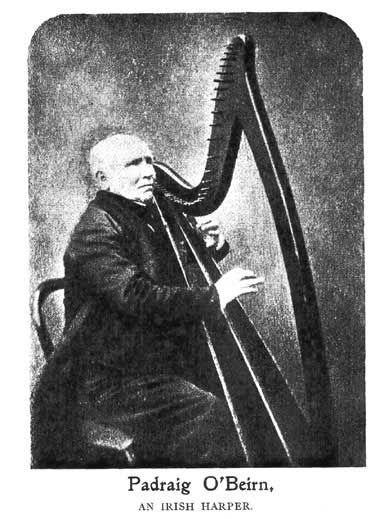

A photograph of Byrne in his later years, from the Ulster Journal of Archaeology vol XVIII, February 1911

‘We ought perhaps to explain that Mr Byrne makes no public exhibition of his skill. It is only in private families and parties that he can be heard and we assure our fellow citizens that the dullness and monotony which so often pervade mixed company cannot be more agreeably relieved by the melodious strains of the Irish Minstrel’.

An advertisement in The Scotsman for the 12 March 1845 provides a good example of his approach to engagements, and it is possible that he did not progress to giving public concerts until much later in his life.

IRISH HARP MUSIC

Mr PATRICK BYRNE the BLIND IRISH HARPER is to be for a short time in Edinburgh, during which he will ATTEND at PRIVATE HOUSES. Address Mrs Thomson’s, 3 West Register Street.

This proved to be significant visit as he was still around Edinburgh on the 1st of April and appeared as The Last Minstrel in a tableau at the Waverly Ball and it was while dressed in his costume that the early calotype pictures of him were made by the photographic pioneers, Hill and Adamson.[7] This was followed in June by his admission as a Master Mason in the Celtic Lodge of Edinburgh and Leith, Number 291 on the register of the Grand Lodge of Scotland. His mason’s certificate which has survived among Patrick’s effects is to date the only known example of a bilingual Gaelic/ English Scottish Masonic document. This was followed four days later by his admission as an honorary Master Mason in the Greenock St Johns Number 176 holding of the Grand Lodge of Scotland.[8] How much longer he stayed in Scotland on this visit is not known, his being in the Clyde port of Greenock may indicate he was heading home, but by December of that year he was certainly back in Ireland and giving a concert in County Armagh.

When Byrne left the Harp Society School, apart from the letter of recommendation attesting to his competence, he was also presented with a harp, a superior version it would seem of the type of instrument that was normally supplied by J Egan to the Belfast Harp Society. These were effectively modern instruments in terms of their construction, but they were still strung with wire. R B Armstrong, who seemed to have had access to the original negatives of Byrne’s portraits, identified thirty seven tuning pins, but with the top five not strung, he then goes on to speculate on a tuning based on thirty two strings. However this needs to be balanced against the evidence from the notes on stringing taken down from Byrne by John Bell which describe a harp of thirty four strings.[9] Whatever the correct number was it does seem clear that Byrne did not use some of the top pins on the Egan. A modern commentator has painted an unflattering opinion of the sound produced by the Egan harps,[10] but this is possibly just an indication of what has been lost in stringing and playing knowledge since it seems to be at odds with those contemporary descriptions of Byrnes playing which refer to ‘ the chords are entirely of wire and when touched lightly emit a tone exceeding wild and sweet’ and ‘It is really a treat to listen to his soft Eolian notes and the effect is heightened by the energy of his manner, for like Marmont’s shepherd ‘he pours his whole soul into the flute’, He only wants the grey hair and the ‘pitying duchess’ to realize Sir Walter Scott’s pictures of his last minstrel’.[11]

With ongoing research, some of Patrick Byrne’s repertoire is emerging from the shadows. We know from McBride’s report to the Harp Society in 1821 that at that point Patrick had learnt sixty tunes, and as he remained at the school for a further eight months or so, then he must have added quite a lot more based on his previous progress. In a brief note to a picture of the harper, which was published in the Ulster Journal of Archaeology in 1911, and which appears have been taken later in Byrnes life than the Edinburgh series of portraits it states that Byrne only played old Irish airs and when asked to play the new tunes invariably replied ‘I never learned them my son’.[12] This may have been true when he first commenced his professional career, but it is clear from the poster for his 1849 concert in Dungannon and other contemporary newspaper reports that his performances normally included ‘Irish, Scotch, and Welch Airs’, unfortunately to date the evidence only names some of the Irish part of this repertoire, although the sort of Scottish material in his repertoire is suggested by a newspaper report that stated that ‘To the airs of some of our plaintive songs and Border Ballads the Irish Harp is admirably adapted and these Mr Byrne touches with a delicacy and pathos which we have seldom if ever heard equalled’.[13]

The New York Emerald account of the playing of Brian Boru’s March as a performance piece has been much quoted over the years, but a more rounded picture of his music comes from the description which appeared along with an engraving of him, in the Illustrated London News, ‘He has a large share of intelligence and humour, and this, with his musical skill, and the correctness of his conduct and general good manners has rendered him very much a favourite everywhere. The style in which he plays the old tunes of Ireland, as ‘Coolin’, ‘Aileen Aroon’ and ‘Gramachree’ as well as those charming melodies of his countryman Carolan – the ‘Foxe’s Sleep’, ‘The Receipt & c, and the various family planxties, is such as to enchain large parties around his instrument for hours at a time’.[14]

To this account can be added a report in the Armagh Guardian from 1845 which describes in some detail a performance. ‘Mr Patrick Byrne, the well known Irish Harper, has been in Tandragee for the last ten days, and performed in the Assembly Rooms of that town on Friday evening, to a highly respectable audience. The rooms were tastefully fitted up for the occasion. precisely at seven o’clock Mr Byrne made his appearance, accompanied by a few friends, who conducted him to a platform erected at one end of the room, after which the concert commenced with ‘The harp that once through Tara’s halls’, which was followed by several other favourite Irish, Scotch and Welsh airs. Then came some comic songs, accompanied by the harp. The audience was subsequently entertained with the story of PAUL DOGHERTY in real Irish style, after which the harpist expressed his thanks for the kindness he received from the inhabitants during his stay among them, and then concluded with ‘God save the Queen’. Mr Byrne left Portadown yesterday morning for the residence of GEORGE CRAWFORD, Esq. Bellvieu House’.[15]

This was not the only indication that Patrick accompanied his own singing, among an inventory of his effects delivered by his nephew shortly after his death to his executor, Evelyn Shirley at Lough Fea, were six pieces of music and two song books,[16] but the firmest evidence that he also sang the more serious songs as well, comes from a general letter of commendation he was given by Edward Bunting.

‘Dear Sir

I am happy to have it in my power to bear testimony to your competency as an Irish Harper. Your having received your musical education in the school of the Belfast Irish Harp Society where you were taught to play according to the method of the ancient harpers is a great advantage and I conceive it to be a matter of much moment that we should have in you a performer yet remaining capable of giving due effect to the primitive airs of our country. Your being able to accompany them with your voice in the words of their native language cannot fail in giving pleasure to those who delight in the simple and beautiful music of Ireland which has been celebrated for so many ages’.

The letter was signed and dated by Bunting on the 29th May 1840 at his Dublin home at 45 Upper Baggott Street. Judging from his papers, Byrne was assiduous in collecting recommendations from all his notable patrons, therefore Buntings reference taken together with the wording of one of Dr James McDonnell’s letters to Bunting when he was encouraging him to publish his 1840 work suggest that Bunting and the harper had probably not met before this time.[17]

Two further pieces of the harper’s repertoire can be surmised from references in his surviving papers, a letter to Byrne at Leamington from James McKnight, dated 8 May 1862 at Derry, mentioned that ‘after I got hold of this old thing (an old harp he had managed to obtain), I found that I had misunderstood the key in which you wished me to write ‘Nanny MacDermot Roe’ and that I wrote it in the wrong key in your book. One of my first attempts on the Cruit was to make out the notes of ‘Nanny’ which I did in the key of A, and I am confident that Carolan must have composed it in this key, as my little instrument almost gave a shout when I touched the right chords. Mr Macpherson too has got a splendid Irish Harp similar to yours, so that when you come to us, we shall not want for music.’[18]

James McKnight also provides the evidence for the second piece, in this case the words to Tighearna Mhaigheo, taken from Hardimans Minstrelsy and copied on 18 February 1861. Both the Gaelic and English translation were made, and in the case of the former, done in a very neat and careful Irish script. It is not clear why an orally taught and blind musician should have wanted his material written down to apparently carry with him, perhaps it was to enable his patrons to make their own copies or he was possibly contemplating publishing his own collection.[19]

In addition to the above named tunes there are two airs in the Bunting manuscripts which he obtained from Patrick, ‘Rose McWard’ and ‘Nurse Putting Child to Sleep’, the former of which may be one of Byrnes own compositions and named after a member of his family. The harper as far as is known was unmarried and had no direct descendants but his father Thomas Byrne had been had been married at least twice and possibly three times over the course of his life so Patrick had a large extended family. His sister Alice, whose mother, like Patrick’s was Mary Fitzpatrick, Thomas Byrnes first wife, married a Patrick Ward and it seems probable that the air ‘Rose McWard’ is connected with that side of the family. In his will Patrick is concerned that his sister Alice and her husband should continue in the farm of Beagh and that it should then pass to their son James.[20] This is an interesting request especially as the harpers executor, Evelyn Shirley was also his landlord, because it is treating the farm as a sort of heritable tenancy, and although Alice and Patrick Ward were obviously running the farm it implies that Patrick was technically the existing tenant. Since he was also keen to see the farm continue to pass on through what in genealogical terms could be called the principle family line, it would also suggest that this was the tenancy that Patrick had ‘inherited’ from his father and that this had therefore been in the families possession for a number of generations.[21] Beagh is actually about a mile north west of modern Greaghlone and about half a mile from what is now called Greaghlone or Beagh Lough, so it would seem to be a reasonable assumption that the Byrne family had been reduced to just tenants on part of the land originally held by their ancestor Pierce O’Birn of the Farney at the start of the 17th century.

When Patrick dictated his will, he made no mention of some of the younger siblings who had already emigrated to America. At that period this was probably a practical necessity in first dealing with relatives you were certain you had rather than those whose whereabouts and condition was less certain. This aspect of the times was well demonstrated by his youngest brother, Christopher who was some forty years Patrick’s junior, who seemed to have lost touch even with some of his own relatives in America. It was only on reading a copy of the New York Tablet, which had repeated an account of one of Patrick’s concerts from the Londonderry Standard in 1863 that Christopher decided to write. At the time, Christopher had enlisted in the 10 th Minnesota Regiment in the Union Army and his letter gives a very good analysis of the political background to the Civil War. Unfortunately, the letter reached its destination shortly after Patrick had died. Christopher, whose regiment at the time of writing was stationed at Vernon Centre, Blue Earth County, protecting the settlers from Indian activity, survived the war and his progress through the war and the ranks (he was promoted to sergeant), can be followed through the Union Army records. On discharge he returned to Minnesota and then drifted westwards as the frontier moved west, (a progress that can be followed in his armypension record), until finally arriving in Idaho, where his descendents still reside.[22]

Patrick Byrne died while on a visit to Dundalk in 1863, he was said to have caught a ‘cold’, which appears to have progressed to pneumonia, he was admitted to the local hospital but continued to decline. He was initially interred in the local graveyard within twenty four hours of his death, which seemed to have been the practice with deaths in the Dundalk hospital at that period. Since this was contrary to the harpers own wishes as recorded in his will, his family, through the offices of Evelyn Shirley Esq of Lough Fea, arranged for a proper oak coffin and he was exhumed and re–interred as hehad requested in the Protestant cemetery at Cloughvalley, by Carrickmacross, with an alter tomb inscribed;–

Here lieth the Body of Patrick Byrne, Harper to H.R.H. The Late Prince Consort Who Departed This Life At Dvndalk April 8. 1863 In The 69th Year Of His Age. May He Rest In Peace Amen’.[23]

His Harp was left to Evelyn Shirley with a wish that it should be preserved in the Great Hall at Lough Fea as an heirloom in the family of Shirley. The current whereabouts of the instrument are uncertain, the present representative of the Shirley’s of Lough Fea remembers that there used to be a harp there, but it is thought that it may have been one of the casualties of a serious fire that occurred at the house in 1966. [However, it has since emerged that the harp survived the fire and is now in private ownership.]* Another item connected with the harper also now apparently no longer at the house is what was described as an ‘Autobiography of Patrick Byrne (the Irish Harper )’ manuscript with printed cuttings relating to him, 8vo. 1864’, that was listed in a printed ‘Catalogue of the Irish Library at Lough Fea’ published by Evelyn Shirley in 1872.[24] It is not among the material from the Library at Lough Fea now owned by the National Library of Ireland, but the library contents are known to have been dispersed on several occasions, the earliest being around 1920, when Dr A S W Rosenbach, the American dealer and collector of rare books and manuscripts was touring country house libraries, including the Lough Fea and Ettington, buying everything he could. All of the purchases made their way into the hands of private collectors in the United States. If the biography has survived and could be found, then it might provide the answers to that crucial gap in the harpers life before he attended the Belfast Harp School.

The contemporary accounts of Patrick frequently described him as ‘the last of a line of minstrels’ or such similar wording. His brother Christopher used the description, probably taken from the newspaper report he had seen before he wrote to his brother. In terms of modern academic accuracy, it was not strictly speaking true, even one of the contemporary press reports in 1856, mentions that ‘the harp music of Ireland is still kept alive by a few practitioners of a very humble kind, who wander about in their own country, chiefly playing to parties assembled in taverns ’, which it then contrasts with its description of Patrick’s performance. There are a number of references to other harpers after Patrick, including Patrick Mourney, another pupil from the harp school, who was still alive in 1882, and H G Farmer recorded seeing an Irish harper in London about 1900, but by that time these appear to have been just itinerant musicians eking out a living.[25] Patrick Byrne certainly was the last of the line of harpers whose traditional status came from playing to the top of the social tree and it is likely that he did actually see himself as the ‘last minstrel’. The fact that he effectively wanted his harp preserved after his death rather than passed on to be played and that although he seems to have instructed some of his amateur patrons, there is absolutely no evidence to suggest that at any time did he attempt to teach another professional would tend to support this view, which even seems to have been held by some of his contemporaries. Among Byrne ’s papers there is a printed ‘Poetic Tribute of Respect Paid Mr Patrick Byrne the Celebrated Irish Harper’ by his esteemed friend Mr James Martin. It is a long piece of nearly eighty lines, but the relevant section reads;–

But why, my friend to England roam

So often from your native home?

And not to Irish youth impart

The knowledge of your matchless ART?

The fairy music of your lyre

Must British hearts with joy inspire;

Through you each Scot or Briton shares

The sweetness of our Irish airs,

Which, from your harp’s melodious chords,

Delights their Ladies fair and Lords.

But from your lovely native shore,

To other countries roam no more.

The poem bears no date but chronologically it sits in a bundle along with another printed item, an address to Patrick following on a meeting at the Shirley Arms Hotel on the 10th January 1855, where it was proposed and carried, that a purse of gold collected from the Inhabitants of his native town of Carrickmacross along with the address neatly engrossed on Vellum should be presented to him. The Velum document is not there but what was printed was a copy with Patrick’s reply, which is probably the nearest it comes to hearing the harper speak and letting him have the last word.

Gentlemen

I feel truly grateful for your kindness to me this day. I believe there is nothing more gratifying to man, no matter how humble, or how exalted his station, than to be well thought of by his friends and countrymen; your gift and address convince me that I have many warm–hearted friends in Farney, and I prise them the more because I had no claim on your generosity, with the exception of my being an unworthy representative of the minstrels of Ireland, and a native of the ancient barony of Farney. I am a Farney man and proud of the name, and although my occupation has brought me under the notice of very many of the nobility and gentry of the three kingdoms, and notwithstanding I have partaken largely of their kindness and hospitality for a period of thirty years. I can assure you, it has always been my fondest wish to spend the latter end of my life in Farney; and lest my kind and honourable friend, Mr Shirley, might not be always here I expect soon to be master of a hut in a corner of Farney where I hope my friends will sometimes visit me and hear me play some of the old national music of Ireland; but should they fail to come to me, I will follow the example of Mahomet of old, who when the hill would not come to him thought it prudent to go to the hill,– I will go to them– and I have made arrangements that when I am laid at rest my Harp shall remain in Farney, for I have bequeathed it to my honourable friend and Patron, E J Shirley, Esq, who I hope will give it room in some corner of his Princely Mansion at Lough Fea, where your children and your grand children may point to it and say,– that instrument belonged to Byrne the Blind Irish Harper.[26]

Patrick Byrne, the first modern harper?

[1] Information from Maurice E. Byrne of Boise, Idaho, USA, who visited his ancestor's grave in 1964.

[2] O’Dalaigh, P.S, ‘Sketches of Farney’, in the Clogher Record, vol 1, No 2, (1954). 59–60. and Schlegel, D.M, ‘An Index to the Rebels of 1641 in the County Monaghan Depositions, in the Clogher Record, vol 15, No 2, (1995). 69–70.

[3] McClelland, A. ‘The Irish Harp Society’ in Ulster Folk Life, 21, (1975); O’Buachalla, B, I mBeal Feirste Cois Cuain, (1968). 66–68.

[4] Public Record Office of Northern Ireland, (PRONI).The Shirley Papers. D/3531/G/1. IRISH HARP SOCIETY BELFAST

This is to certify that the bearer Patrick

Byrne from Kings Court in the County Cavan

and a native of the Barony of Farney in the County Monaghan

was admitted a pupil of the Irish Harp Society

of Belfast on the 21st February 1820, and that

upon examination of his musical proficiency, he

is deemed qualified to play in public and he

is therefore recommended to all lovers of our

national Instrument and Music.

As an acknowledgement of his good deportment

and diligence as a scholar of the house, the

Society has presented him a Harp.

[5] PRONI, D/3531/G/1, This was presumably Washington Sewallis Shirley, Ninth Earl Ferrers who died on the 13th March 1859 and whose black edged death notification sent to Patrick is still among his kept correspondence in bundle D/3531/G/5.

[6] PRONI, D/3531/G/1, The certificate of appointment is dated at Buckingham Palace on the 6th January 1841; Ballina Chronicle 12th September 1849.

[7] According to an account of the Ball published in The Illustrated London News of 12th April 1845, ‘At the conclusion of the tableau, Mr Byrne played a national melody; and, subsequently, in one of the anti–rooms, attracted around him groups of the company, whose picturesque dresses rendered the scene peculiarly interesting’.

The most complete collection of the calotype studies of Patrick Byrne are those in the collection of Scottish National Portrait Gallery, and published in their catalogue of the David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson Calotypes. (Edinburgh 1981). There are six pictures altogether, four with the harper seated in a playing position and all bar one with him in the costume of ‘the last minstrel’.

[8] PRONI, D/3531/G/1. The certificate is ornately engraved and printed so the bilingual form was presumably the usual form used by the ‘Celtic Lodge’, Patrick has signed his ‘mark’ at the edge of the document. The Greenock Lodge certificate was also bilingual, but in its case, English and Latin.

[9] Armstrong, R.B, The Irish and the Highland Harps;, (1904), Supplemental facing page 136; John Bell’s Notebook in the Farmer Collection, Glasgow University Library, published by H G Farmer in Music and Letters, Vol 24, (1943).

[10] Rimmer, J, The Irish Harp, (1977), 67.

[11] Edinburgh Advertiser 19th December 1837.

[12] Ulster Journal of Archaeology, Vol XVII, (February–November 1911). The note is by F J Biggar but there is no indication where he got the picture which shows a much older man than the Edinburgh series. Among Patrick’s correspondence in bundle D/3531/G/5 there are three letters, all from early 1862, thanking him for ‘the picture’ of him. One of them from his sister Catherine Byrne in Ohio, USA, refers to having received the picture with a letter from him dated 20th October 1861, and also remarks on how well he looked at 64 years of age. This would be commensurate with his appearance in this picture but if it is assumed that it was taken around 1860/61 introduces a third potential birth date of 1796.

[13] Edinburgh Advertiser 19th December 1837.

[14] The Illustrated London News, 11th October 1856, 371. It also includes an engraving of Byrne seated at his harp. This picture is very similar to the engraving of Byrne published in F O’Neill’s Irish Minstrels and Musicians, (1913), 80. The News version is superior as far as Byrne is concerned but less so with his harp, but may have been the source which was re engraved for the O’Neill publication with a more accurate depiction of the harp but poorer version of Byrne.

[15] Armagh Guardian 16th December 1845.

[16] PRONI, D/3531/G/6

[17] PRONI, D/3531/G/1; Fox, C.M, Annals of the Irish Harpers, (1911), 135–136.

[18] PRONI, D/3531/G/5

[19] PRONI, D/3531/G/3

[20] The family tradition that was passed down suggested that Patrick got his musical genius from his mothers side of the family. His sister Ann, known in the family as Anna Ruha, because she had red hair was also known as ‘melodious’ presumably because of her musical ability. Information from Maurice E Byrne of Idaho, USA.

[21] PRONI, D/3531/G/6, a witnessed copy of the will which was drawn up at Lower Ettington on the 9th May 1859. An earlier will of 1846 with codicil added in 1856 is among the Shirley of Ettington papers deposited in the Warwickshire County Record Office catalogued as CR229/ box 18/5.

[22] PRONI, D 3531/G/6; National Archives of the US, Military and Pensions Records, search No 674652 and 676158.

[23] Shirley, E.P, ‘The History of the County of Monaghan’, (1879), 530.

[24] Shirley, E.P, ‘Catalogue of the Irish Library at Lough Fea’,(1872), 31, on National Library of Scotland Microfilm Mf.66 (5 [2]). Among a list of the late Patrick Byrnes effects with value, compiled by E P Shirley on the 29th September 1863, are 3 MS Music Books, 4 Books of printed items in a portfolio and 3 Books of Newspaper Cuttings, and it was probably these cuttings which were added into the Biography. Additional information regarding Lough Fea from Major J E Shirley. Isle of Man.

[25] Farmer, H.G, ‘Some Notes on the Irish Harp’, in Music and Letters, Vol 24, (1943), 107.

[26] PRNOI, D/3531/G/2

* In October 2017 the editor@wirestrungharp was contacted by the performing artist Baby Dee who related the story of how, about the year 1974 or 5, she had purchased the harp in a junk shop in Dublin. It would appear that after the fire much of the fire–damaged goods and furnishings were cleared, possibly being sold off as a job lot, and entered into the ‘second hand’, or ‘junk shop’ trade where the harp circulated for a while. Dee took the smoke—blackened and damaged instrument to New York where it was cleaned and repaired by the luthier Noah Wolfe. Examination of the details surviving on this harp leave little doubt that it is indeed the one that had belonged for so many years to Patrick Byrne. The harp is now in the keeping of a third party.

I would also like to thank Ann and Charlie Heymann of Minnesota, USA, and Professor Ruth Ann Harris of Boston, USA, all of whom have their own interests in Patrick Byrne and have freely exchanged ideas.

Keith Sanger, 3 August, 2006

Except where otherwise noted, content on this site is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available by contacting us at editor@wirestrungharp.com.