The origin of the first European triangular framed harps is still an unresolved question in terms of there being a uniform view of the instrument’s early history. More specifically, in regard to its appearance in the British Isles, the argument divides into the instrument having evolved outwith these islands and therefore arriving in a more or less developed form, and the proponents of an insular origin. Even if this latter proposition is accepted there remains the questions, why, how and where in Britain it could have evolved. It is not intended to attempt the impossible and give a definitive answer to these questions here. The most that can be achieved is to briefly sketch the background, and in the prime purpose of this paper, to explore a logical structural development from one of the forms found among the early carved Scottish stones to the instrument we know today as the medieval clarsach. This is by its nature a very speculative exercise.

Detail of the harp carved into the Nigg Stone. Click on the image to view a larger image of the harp and more of the surrounding stone carving.

(Photograph by Keith Sanger, © WireStrungharp.com.)

As an introduction it is interesting to summarise the comments of some of the more serious works from the past century. Curt Sachs in his History of Musical Instruments, published in 1942, proposed that Europe could be divided into two zones, a southern zone in which the stringed instruments (other than the harp), took the form of ‘lutes’ that is with necks, and a northern zone in which they took the form of ‘lyres’, that is with a two armed body with crossbar at the top. He then continues to suggest that these two zones point to a twofold origin of early medieval instruments, the first from an uncertain source feeding the north of Europe and the second probably coming from the area of southwestern Asia in which rear tuning pegs are found. (as apposed to the lateral pegs of the Arabo–Persian district). Under the heading ‘The Harp’ he states;— The question, often asked and never satisfactorily answered, of what kinds of stringed instruments Central and North Europe had in antiquity and in the early middle ages, depends on the interpretation of a few philological and pictorial sources. This is a statement that could still hold true today, but unfortunately Sachs subsequent attempt to clarify the situation, while making one or two valid points, also manages to demonstrate the pitfalls that arise from failure to realise that the Germanic word ‘harp’ originally described the instrument we now call a lyre. [1]

In 1965 the fourth edition of F.W. Galpin’s Old English Instruments of Music

was published with extensive revision by Thurston Dart. Despite its title the book’s chapter on the Rote and Harp also reviews the evidence for these instruments in Ireland, Scotland and Wales. When dealing with Ireland the authors recognise the excesses of some of the claims for the Irish Harp’s antiquity made by Gratton Flood, but fail to avoid the frequent pitfall of failing to appreciate that the original Anglo Saxon harp was not the familiar triangular modern instrument. This led to a confused section where after suggesting an English or northern source for what they called the ‘true’ harp they extend its origins to include the Scandinavians and by implication credit them with its introduction to Ireland.[2]

Fortunately in 1970 Rupert and Myrtle Bruce–Mitford published their paper on their new reconstruction of the Sutton Hoo Lyre and in it at last clearly established a definitive picture of the instrument originally known as a harp. However when they come to discuss the ’true harp’ they state;— The problem of its origin is one of the most baffling and important in early musicology. There seems, however, to be agreement that the frame harp was invented, or evolved in the British Isles

.

The earliest pictures of the true harp are from the ninth/tenth century. It is depicted in developed form, resting on the ground and as tall as the player, on standing stones thought to be of this date in Scotland, at Nigg in Ross–shire and Dupplin, in Perthshire. The small form, held on the knees, is depicted in many Anglo–Saxon manuscripts, one of the earliest representations in which the instrument is given a sub–quadrangular form by its bent fore–pillar, being in the Bodleian Caedmon manuscript, Junius XI ( late 10th century). As the harp seems to develop early in size in the north, and since the Irish stones and crosses show a range of hybrid forms, perhaps the place of origin was Northumbria, where diverse influences met. It was to become an instrument equally common with Saxons and Celts’.[3]

The Bruce–Mitfords failed to indicate what their statement regarding agreement that the true Harp was invented or evolved in the British Isles was based on but it is probably significant that the year before their paper was published, two books had appeared. The larger of the two ’The Harp’ by Roslyn Rensch briefly touched on Galpin’s suggestions and a few other possibilities before finally sitting on the fence with the statement that any people who owned a bow had the prototype of the frame harp of western Europe. The second, much smaller book was ’The Irish Harp’ by Joan Rimmer, primarily as the title indicated a survey of the Irish instruments. Its brief but concise introduction noted that on iconographical evidence the fully–framed triangular harp appeared in the ninth century and that the accuracy of depiction seems to be related to some degree of Celtic or British or at any rate north–west European influence.[4]

Both these books of course represented the careful views of a published work, although at least one of the authors, Roslyn Rensch in a private letter appeared to be more positively in favour of an insular origin. This did not however carry through to her later more comprehensive book, Harps &Harpists published in 1989, where she managed to avoid dealing with the subject altogether.

By this time the subject of the origin of the triangular frame harp had already been tackled head on by James Porter in an essay on the problem of Pictish music published in 1983. In his paper most of the early Scottish sculptured stones were reviewed, including one very optimistic claim for a harp on a fragment of stone at St Andrews. Despite the dubiousness of that particular stone, which I do not think Professor Porter had actually seen (he was going on a published reconstruction), this paper advanced the first clear, albeit qualified, argument for the Pictish development of a triangular frame harp.[5] This suggestion was given further impetus by John Bannerman in 1991, John Purser in 1992, and Sanger and Kinnaird also 1992,[6] although opinions are still divided and the idea has yet to achieve universal acceptance.[7] Therefore, prior to moving to any discussion of the nature and development of a Pictish instrument it is advisable to examine three related areas where there is a general consensus and consider the implications for a triangular Pictish harp.

Early Irish literature, whether contemporary or later recordings of oral tradition, makes frequent references to the use of stringed instruments, a usage that is confirmed by the account of Gerald of Wales, written around 1183–84. Without exception, irrespective of the instrument, when the strings are mentioned they are said to be made of brass. In reality the composition of the medieval metal was closer to what would now be called bronze, and in the descriptive poetic Gaelic used by the Irish poets the strings might also be referred to as ’golden’. However, irrespective of the exact composition of the material, it would appear that the Irish, in contrast to their neighbours, preferred metal strings for all their instruments. This is in clear contrast to the rest of northwest Europe where metal strings were primarily associated with pig–snout psalteries.[8]

The nature of early string instruments in Wales poses a number of problems. Evidence from medieval poetry indicates that there was a flourishing bardic tradition and by implication that in common with its neighbours this was delivered to a musical accompaniment, but evidence of the exact type of instruments used is generally lacking. Unlike Ireland and Scotland there are no carved stones nor finds comparable to the Anglo–Saxon grave goods. It is not until the comments of Gerald of Wales, dated around 1185–8 and the more explicit remarks of the later fourteenth century poets, that a clearer picture emerges, albeit one that is still open to revision.

The evidence suggests that by this period, Welsh instruments and musicians were using horsehair strings, probably with leather sound boards, although this latter part may still be open to interpretation. What can be said is that in late eighteenth century Wales a harp hollowed out from wood with a leather sound board was still being played in some parts of the country.[9] It does therefore seem likely that this was a late survival of a horsehair–strung triangular harp which had been played by the indigenous peoples of mainland Britain, but which by the fourteenth century was restricted to Wales where it was already being regarded by some people as inferior to the other harps then available from Ireland to the west and across the border from England in the east.

The final part of this trilogy concerns the instrument known to the Anglo–Saxons as a ’harp’. All the evidence to date suggests that this instrument was originally what we would now term a lyre, but at some point this Anglo–Saxon word was transferred to describe the triangular chordophone we now call a harp. How and why this occurred is like the origin of the triangular European frame harp, still a matter of conjecture, but we are probably on safe ground in suggesting that it happened between the years 900 to 1100 AD.

Since the reconstruction of the Sutton Hoo lyre and the identification of its common origin with the other European lyres further excavations have yielded additional evidence from Anglo–Saxon sites for this type of chordophone. However, despite a request by one of the foremost experts on the Anglo–Saxon instruments to his archaeological colleagues to look out for the triangular frame harp in their excavations, in the period up to the eleventh century no evidence for the triangular instrument has surfaced to date.[10] This is in clear contrast to the situation from the twelve century onwards, when evidence for a triangular chordophone rather than the Anglo–Saxon or Germanic ’harp’ becomes more common in the southern part of Britain.[11]

Contrary to the situation in Ireland and Scotland, the early carved monuments of pre–Norman England and Wales rarely show representations of musical instruments, a factor that does not seem to have produced much academic curiosity. While this description of a geographical division borders on being a generalisation, it is worth noting that the few exceptions, placed in context, arguably add to rather than detract from that division. If a lyre–like instrument on a cross slab on the Isle of Man is removed from consideration, then there seem to be only two examples of musicians shown on English monuments and both are found in the north of what is now modern England, although at the time of their carving could probably more aptly be described as part of the broad boundary between Scandinavian York and Anglo–Saxon Northumbria. This is reflected in the monuments which seem to be relatively close in both period and, being some twenty miles apart, physical proximity.

The fragment at Sockburn Du, just south of Darlington, North Yorkshire, has been firmly placed among Viking age sculpture and has what is described as David playing his lyre and this is probably the instrument that the sculpture is meant to convey.[12] Somewhat further south at Masham, still in North Yorkshire, the sculpture is more complex. A very worn panel on a sculpted column dated to the ninth century has also been identified as David the Psalmist together with three supporting figures. Despite the wear, the principle figure of David is clearly playing a round top lyre and a good case has also been made for one of the subsidiary figures having a small triangular harp.[13]

If this identification is accepted, then the sculptor must have had some awareness of both instruments. However, placing an Anglo–Saxon lyre in the hands of the King David figure implies that, although aware of the triangular chordophone, the sculptor did not yet regard it as suitable for supplanting the lyre in the hands of the king. This is much as would be expected in an area towards the margins of the Anglo–Saxon cultural milieu, whose influence had probably been weakened by the intervention of Danish Vikings. The subsequent fluctuating power struggles for control of what is now northern England between Danes, the Northumbrians, the Kings of Strathclyde and the united Kingdoms of the Picts and Scots would have provided an additional stir to the mix of cultural influences available to that geographical region.

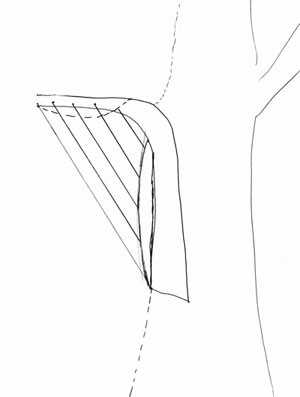

As this clearly amounts to a speculative exercise it is therefore possible to start by selecting the most appropriate representation of a harp from the surviving Pictish carvings, albeit by adding some justifications. The Cross Slab at Nigg, now for preservation purposes relocated inside the Kirk, is normally assigned a Class 2 designation due to its having some Christian symbolism. It is carved on both sides with a Cross on what is usually described as the front and on the back some David–associated material including the triangular harp. Among the advantages of choosing this carving is that it is one of, and possibly the earliest, representations of a ’Pictish’ harp. Furthermore, as in many of the Pictish carvings while being interpreted as a ’King David’ identifier, the harp is depicted as a stand alone instrument and not possibly distorted by being in the hands of a player. (see Black and white photo)

Figure 1

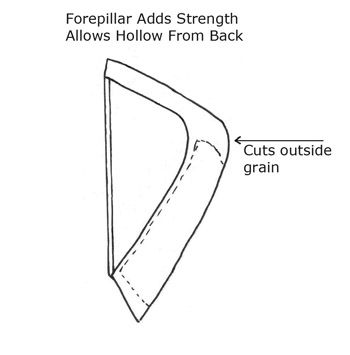

As shown the the harp has a straight string bar with a thin straight fore pillar. Excluding the pillar, the string bar and sound box have a very distinctive shape but one which could certainly have been cut directly from a section of tree trunk which included one of the side branches (see Figure 1). Our early ancestors had a long history of managing woodlands and the beginning of the practices of coppicing and pollarding is almost lost in the mists of time. Likewise selecting timber which already meets the shape you desire is equally as old. The bent section from keel to prow of early boats was often sourced that way and recent work has confirmed that the fore pillars of the Queen Mary and Lamont Harps used suitably curved sections of wood.

Using a one–piece construction to make a ’Nigg’ harp while avoiding a manufactured joint at the junction of the string bar and the top of the sound box depends on the integral strength of the original wood and this leads to the next assumption that the sound box was hollowed out from the front and not the back. If such a one piece construction had been hollowed out from the back to form a wooden soundboard, to appropriately thin the top end of that soundboard would have required cutting through the stronger heartwood leading off to the branch thereby weakening and removing the advantage of using a one piece construction (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

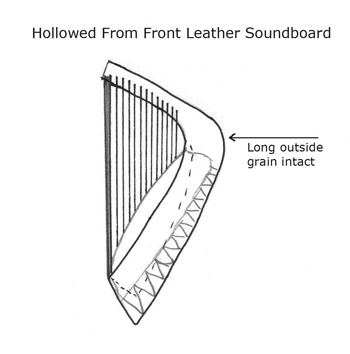

Using a leather soundboard does fit with the idea of a sound box hollowed from the front and the attributes of such a sound board also have the additional advantage that it only needs a small amount of space behind the top part, again avoiding cutting across the heartwood (see Figure 3). As long as there is sufficient space for the leather soundboard to vibrate it will sound and it is possible to speculate that the overall timbre of such a soundboard would more closely resemble a banjo or some of the African instruments which also use a ’skin’ resonator. This does raise the question of how strong such a soundboard might be and how it would be fitted and once again it is possible to use some historical precedents.

Figure 3

Animal skins especially when processed into tanned leather were one of mankind’s earliest raw materials. Depending upon the nature of the skin and its treatment it could be soft enough for fine clothing or hard enough to serve as some protection to the body during battles. Turning to archaeological evidence, a Bronze age leather shield has been found in a bog at Cloonbrin, Co. Longford and wooden moulds for production of such shields are also known from elsewhere. The Cloonbrin shield was made from leather 5–6 mm thick with a sewn–on leather handle and an otherwise unsupported diameter of circa 50 centimeters.[14] None of this is very surprising as even today the traditional Zulu shield is made of cowhide with a single vertical stick serving as handhold and providing some vertical stiffening.

Fitting a leather soundboard would also have been straightforward using techniques common at that period. The leather simply stretched across the box and secured by tightly lacing it around the back of the box. If laced on while wet it would have tightened further as it dried and shrank. A harp with leather soundboard is unlikely to have been metal strung so that leaves a choice of gut or horsehair. The horses shown on the Pictish stones certainly have tails of a suitable length and horsehair was at one time used for archery bow strings so would have had the strength required. Furthermore when looking to Wales what little evidence we have from there suggests a combination of leather soundboards and horsehair strings.

Although the discussion so far has concentrated on a possible interpretation and construction of the harp on the Nigg Cross slab, the fact that the instrument is depicted on its own means that it is difficult to drawer any conclusions about the size and number of strings. On the original carving it is possible to count seven strings, but it is always unsafe to assume that any of the early representations of stringed instruments show the correct numbers of strings as the size of the image and the nature of the medium dictate how much detail the artist can actually show.

Looking at the other Pictish carvings which do show the harps in the hands of the players suggests that relative to the size of players they range in size from an instrument playable on the lap, (Lethendy), to an instrument resting on the ground and reaching to the shoulder of a seated player, (Dupplin). Since instruments tended to grow in size over time and the Nigg stone is one of the earliest showing a harp, then it is more likely to be at the smaller end of the range. Even at that size though, more than the seven strings shown would be likely and around twenty or so is quite feasible.

It is possible from the structure of the ’Pictish harp’ just proposed to move on to suggest a logical and chronological progression from an instrument with a leather soundboard and one piece sound box and string bar to the more familiar jointed two piece construction with a wooden soundboard. The limitations of leather soundboards due to rising tension from increasing the number of strings and thereby the size of the instruments along with changing string materials would have instigated a change to the use of a stronger soundboard material. Just as using naturally grown pre–shaped sections of timber was an established technique, so too was the concept of starting with a log and hollowing it out. Such a technique had already been used for making log boats and coffins among other such one piece ’box’ constructions so that concept would not have needed any new techniques.

Figure 4

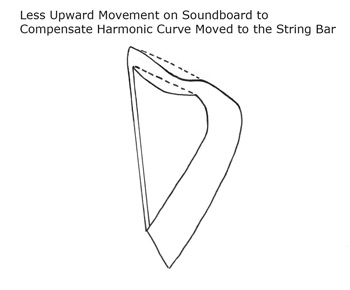

Moving from a leather soundboard to a wooden soundboard made by hollowing the wooden block out from the back would though have required some other changes to the structure of the harps. For the soundboard to work required the space behind it to extend right the top of the board, which meant cutting across the ’heartwood’ leading to the branch used as a string bar severely reducing its strength. Therefore instead of the box and string bar consisting of one continuous piece of wood, a two piece jointed construction was necessary. Although all soundboards to some extent rise under the tension of the strings, a leather soundboard, even with the likely addition of a wooden slat under the leather to reinforce the stringholes and spread the load, would have risen considerably more than wood.

Figure 5

That would have had the effect, despite that harp having a straight string bar, of producing a harmonic curve at the bottom of the strings. A curve which would have been greatly reduced through using a wooden soundboard and especially as the harps increased in size resulted in the introduction of a harmonic curve at the string bar (see Figure 4).

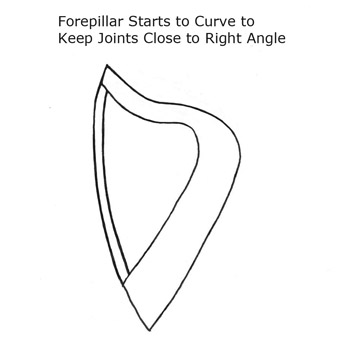

Ultimately as this created a curved string bar one of the advantages of also introducing a curve to the forpillar would help to keep the mortise and tenon joint at the junction of the pillar and stringbar closer a right angle despite the curve (see Figure 5).

This is of course all very speculative and the original draft of this paper along with the drawings date to around 1994 when sitting in the shade of some trees I realised that there was something very familiar about the shape of part of one of those trees. The question of the ’Pictish’ harps continued to occupy my thoughts and they were further condensed in a talk I gave in 2005.[15] Since then there have been a number of positive developments starting with the evidence from the 2010 excavations at High Pasture Caves on Skye that the ’proto picts’, that is the ancestors of the people who subsequently were to become known as ’Picts’ were using stringed instruments as far back as 450–550 BC. Moving on to the people known as Picts, a series of excavations at Portmahomack culminated in a publication in 2008 which demonstrated that it was the site of a Pictish monastery dating from the sixth Century and that there was evidence of leather working for the production of vellum.[16] Taken together with the recent evidence that the earliest pre Christian Class 1 Pictish stones could be third/fourth Century[17] raises the possibility that the Class 2 stones like the one at Nigg, which have Christian symbolism but like the Class 1 stones have previously been dated mostly by Art Historical means, might also be earlier than usually credited.

[1] Sachs, Curt The History of Musical Instruments (1942)

[2] Galpin, F W. Old English Instruments of Music, (4th edition. 1965), see also, O Anderson, Francis W. Galpin and the Triangular Harps, Galpin Society Journal. Vol 19. 1966. 57–60.

[3] Bruce–Mitford R & M, The Sutton Hoo Lyre, Beowulf, and the Origins of the Frame Harp. Antiquity, XLIV (1970) 7–13.

[4] Rensch, Roslyn. The Harp (1969), 28–31; Rimmer, Joan. The Irish Harp (2nd edition. 1977), 13.

[5] Porter, J. Harps, pipes and Pictish Stones : The Problems of Pictish Music. Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology 4, Essays in honour of Peter Crossley–Holland. (1983), 243–267.

[6] Bannerman, J. The Clarsach and the Clarsair, Scottish Studies, vol 30 (1991); Purser, J. Scotland's Music, (1992); Sanger, K & Kinnaird, A Tree of Strings/Crann nan Teud, (1992)

[7] Ross, A. Harps of Their Owne Sort? A Reassessment of Pictish Chordophone Depictions, in Cambrian Medieval Celtic Studies, 36, Winter 1998.

[8] Page, Christopher. Voices And Instruments Of The Middle Ages. 1987. 216–219.

[9] Johnston, D R. Gwaith Iolo Goch. 143–146. ;Jones, E. Musical and Poetical Relicks of the Welsh Bards. (1825 edition), Vol 1, 102–103.

[10] Bruce–Mitford R & M, The Sutton Hoo Lyre, Beowulf, and the Origins of the Frame Harp. In Antiquity, XLIV, 1970. 9–10; Lawson, G. Harps and Lyres. In Current Archaeology, 52. (September 1975). 140; Lawson, G. The Lyre from Grave 22, in East Anglian Archaeology, Report No 7, Norfolk. 1978. 21, 63–64, 87–110.

[11] Fry, D K. Anglo–Saxon Lyre Tuning Pegs from Whitby, Yorkshire, in Medieval Archaeology, 20, 1976. 137–139; Lawson, G. Mediaeval Tuning Pegs from Whitby, Yorkshire, in Medieval Archaeology, 22, 1978. 139–141.

[12] Bailey, R N. Viking Age Sculpture in Northern England, (1980). 155.

[13] Lawson, G. An Anglo–Saxon harp and lyre of the ninth century, in Widness, D.R. and Wolpert, R.F ed, Music and tradition essays on Asian and other musics presented to Laurence Picken. (1981). 229–244.

[14] O’Kelly, M and O’Kelly C. Early Ireland– An Introduction to Irish History. (1989). p170

[15] Sanger K, Myth and Mist. (5 April 2005). https://independent.academia.edu/KeithSanger/Talks Accessed 19 April 2019.

[16] Carver, Martin. An Iona of the East; the early–medieval monastry at Portmahomack, Tarbat Ness. (2004) http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/1830/1/carverm2.pdf Accessed 19 April 2019.

[17] Noble, G. Goldberg, M and Hamilton, D. The Development of the Pictish symbol system; inscribing identity beyond the edge of Empire. Antiquity, Volume 92. Issue 365 (October 2018). pp 1329–1348 https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/antiquity/article/development-of-the-pictish-symbol-system-inscribing-identity-beyond-the-edges-of-empire/4F09B9C943A1C29F226591A20BEC5248 Accessed 19 April 2019.

Submitted by Keith Sanger, 19 April, 2019.

Except where otherwise noted, content on this site is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available by contacting us at editor@wirestrungharp.com.