by Nicholas Carolan

First published in ‘Ceol, A Journal of Irish Music’, Volume VII, numbers 1 & 2, (December 1984)

Reprinted here by kind permission of the author.

The Irish harp of the eighteenth century, large, difficult to make and play, expensive and hard to keep in order, was yet, apart from its musical attributes, a certain mark of status and a decoration to a house, an instrument of sufficient worth to engage the attention of a company. In an age of frequent domestic musical performance, it was an instrument of the superior professional itinerant musician and of the better–off musical amateur.

Contemporary writings give evidence that there were some hundreds of harps in the country during the century. ‘In every [gentleman’s] house was one or two harps...I do not confine this custom to ancient times; it was observed forty years ago, and still subsists in many parts of the kingdom,’ wrote the Limerick historian Dr. Sylvester O’Halloran for one, in 1772.[1] O’Halloran, born in 1728, was himself the owner of an old and interesting harp. After his death, it was burnt as firewood by a servant.[2]

Fire, damp, woodworm and neglect, the self–destruction inherent in an instrument tuned at a terrific tension, the gradual ruin of the Irish country house, and other causes, have so reduced the number of lrish harps that only a handful have survived to the present day. In her monograph The Irish Harp (3rd ed. l984) Joan Rimmer lists just seven extant pre–twentieth century specimens of the traditional form.

Two hitherto unnoticed examples have gone on exhibition in Malahide Castle, Co. Dublin, in recent years, and are described and illustrated below. The castle was formerly the home of the Talbot family and is now in public ownership, administered by Dublin Tourism and Ireland East Tourism, but the harps in question have no intrinsic connection with the castle. They were loaned for exhibition there by their owner, Mr. William Kearney.

Although both instruments are of the high–headed type, their very different personalities imply distinctly different origins, and suggest that a great range of differences would be seen in the Irish high–headed harp if more examples had survived.

Paint and varnish have made visual identification of the woods and metals difficult, and for lack of objective evidence on the age of the instruments, dating must rely on subjective comparison with other surviving specimens and illustrations.

I am grateful to Liam McNulty for photographing the harps, to Ted Colgan for identifying their materials, to Mr. William Kearney for information and permission to photograph, and to Ms. Ann Chambers, administrator of Malahide Castle, and her staff for their help and courtesy.

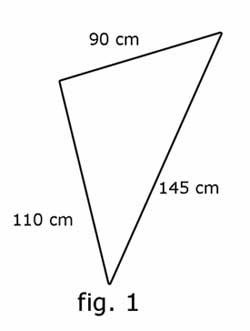

Probably of the eighteenth century and clearly the older of the two, is a large functional instrument, of journeyman construction and with perfunctory decoration, but with a strength and character given by the distinctive soundbox. It is now unstrung but is likely to have had a loud strong sound. Measurements[3] from apex to apex are in fig. l. The belly and sides of the soundbox, the neck and the forepillar are pine; the back of the soundbox seems to be beech. The harp has been partly grained with dark brown paint and varnished, and there is yellow paint along the top of the neck and the front of the forepillar. Joins are made by nails with the exceptions noted below.

The tapering built–up soundbox, 37 cm wide and 6 cm deep at the side of the straight bottom, and 10 cm wide and 14 cm deep at the top, is made of five or possibly six pieces forming belly and flat sides, three pieces forming the back, a squared flush block at the top and another, larger but with a small projecting foot, at the bottom. The pieces are about 1½ cm thick. The box is bound with three copper bands, and a copper strip, with 40 perforations to take the strings, runs down the centre of the chamfered curving belly. The perforations are each 2 cm apart. Woodworm has affected the mortise–and–tenon joint of the bottom block and forepillar, and they are now held together by metal braces. The flat back has two circular sound holes 10 cm in diameter.

Photograph of Harp no. 1

Inside the soundbox a perforated wooden lath runs down the back of the belly behind the copper strip. The ends of a few strings, badly corroded steel above or rigid brass of about 1/16 inch guage below, are held in this, and show how the strings were fastened. Each has been wrapped once or twice around a short hardwood toggle, 2 cm long, possibly beech, and bound to it with hemp or flax.

The neck, bevelled along the top, is 3½ cm thick and from 7 to 11 cm in breadth, with a turned boss nailed to the finial and another to the mid-neck crest. It is screwed to the top block of the soundbox and mortised underneath to take the tenon of the forepillar. Neck and forepillar are warped to the left.[4] The inset neckbands seem to be of some ferrous material. That on the right is made of three butted pieces, that on the left of two. There are 36 peg–holes and 36 tuning pegs, squared on the right and rounded with perforation on the left. On the bass side l5 are steel, on the treble, 21 are brass. The vibrating length of the longest string would have been 115 cm, of the shortest, 8 cm.

The almost straight forepillar, 3½ cm thick and narrowing in breadth as it descends from 12 to 9 cm, is bevelled along the back and has a strip of wood attached along the front. The harp is permanently supported in a wooden pedestal which is clearly not contemporary with it. The instrument was bought at auction in 1975 in Ardee. Co. Louth, and had come from a country house in the immediate vicinity.

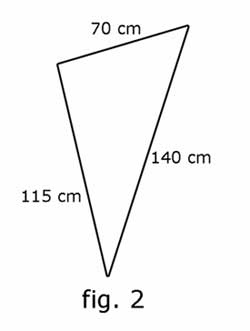

Possibly of the eighteenth century, possibly later, is also large but more carefully crafted and with more expensive material, and has little of the medieval character of the other instrument. Its maker could believably have turned his hand to high-quality cabinet making or violin making. The visual effect is more delicate than that of harp l, and the remaining 22 strings, all steel and on the treble side but badly corroded and slack, suggest that it had a fairly light ringing sound. Measurements from apex to apex are in fig. 2. The forepillar and soundbox blocks are of pitch pine, and the remainder of the soundbox and neck seem to be sycamore. The finish is french polish and light brown varnish, and the soundbox belly is wreathed with dark green painted shamrocks and gilded on its perimeter. Joins are made by nails with the exceptions noted below.

Photograph of Harp no. 2

The tapering built–up soundbox, 29 cm wide across the rounded bottom and 8½ cm deep at its side, l2 cm wide and 10½ cm deep at the top, is made of a single–piece inset gently curving belly, a single–piece inset flat back with two oval sound–holes 9 cm in horizontal diameter, two flat sides holding in belly and back, a decoratively shaped projecting block at the top and another larger one at the bottom, rounded on each side with a projecting squared foot. The top block is mortised to take the tenon of the neck. Both blocks are rebated to take the other parts of the box which are about l cm thick. A brass strip with 37 perforations runs down the centre of the belly, backed by a wooden lath. The perforations are each 2½ cm apart.

Inside the soundbox the ends of the strings are fixed with thread around short hardwood toggles, each l cm long, possibly laburnum.

The neck is 4 cm thick and from 6 to 8 cm in breadth with a carved rosette dowelled in to the left of the finial. Another was on the right but is now missing. There is a decorative gouge on each side above the brass single–piece inset neck bands which have 36 peg–holes and 35 brass tuning pegs. squared on the right and rounded with perforations on the left. A tenon brings it to the forepillar. Neck and forepillar are warped to the left. The vibrating length of the longest string would have been 110 cm, of the shortest is 4 cm.

The curving forepillar, 3½ cm thick and from 8 to 6 cm in breadth as it tapers downwards, is bevelled along the back and decoratively rebated along the front. A mortise at the top takes the tenon of the neck, a tenon at the bottom fits into a mortise in the foot.

The centre of the belly has lifted out of position and the instrument could not be played in its present state. The harp was bought at auction in 1967 in Belfast but nothing is known of its origins.

[1] Sylvester 0’Halloran, An Introduction to the History and Antiquities of Ireland, Dublin I772, p.75.

[2] Edward Bunting, A General Collection of the Ancient Music of lreland, London 1809, p.26n.

[3] Measurements are approximate and are given for their acoustic implications rather than for construction. Where applicable, they are outside measurements.

[4] Right and left are from the viewpoint of the playing harper.

© 1984 and 2011 by Nicholas Carolan, all rights reserved.