Robert Bruce Armstrong’s conclusions relating to the ‘history’ of this instrument have remained the orthodox view ever since they were first published in his The Irish and the Highland Harps in 1904. While Armstrong’s assessment was reasonable based on the information he had at that time, a deeper study of the background of the harp and it’s former owner Edward Lindsay shows that most of the questions first raised by Armstrong can be satisfactorily answered. This in turn allows the focus to move onto the more positive evidence presented by the harp itself and it’s probable one–time owner Arthur O’Neill.

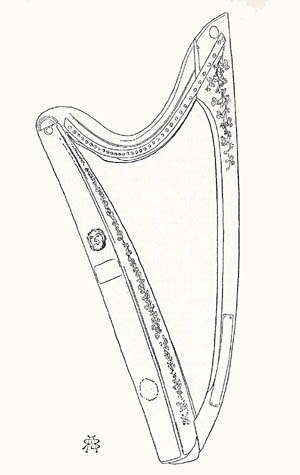

Drawing of the Belfast Museum Harp by Robert Bruce Armstrong, from The Irish and Highland Harps

In common with a number of the surviving wire strung harps, which bear names owing more to the unbridled enthusiasm of the early antiquarians rather than historical fact, the ‘O’Neill harp’, currently in the Ulster Museum in Belfast, has a name which has served more as a label rather than a serious belief. Due to the presence of what appears to be the hand of O’Neill among some carvings on the top of the harmonic curve, modern historians have tended to accept that the instrument may at some point have belonged to someone called O’Neill, but not Arthur O’Neill, one of the best known of the last harpers. Indeed in her work on the Irish harps Joan Rimmer sums it up with the unequivocal statement that ‘There is no evidence that this harp belonged to Arthur O’Neill’.[1] Robert Bruce Armstrong in his work on the Irish Harps gives a much fuller description of the actual instrument along with it’s background, before coming to a more open conclusion that ‘unless direct proof is forthcoming, Mr Lindsay’s statement should be received with grave suspicion, or altogether discredited’.[2] His view however changes to become far more negative in his later manuscript notes after obtaining further information on Mr Lindsay, the instrument’s one–time owner.

Therefore it is probably advisable to review what is known about the instrument, its history, ‘Mr Lindsay’ and Arthur O’Neill’s harp (or harps) before suggesting that the harp itself does in fact provide some evidence in favour of it having been at some point in the possession of Arthur O’Neill.

Robert Bruce Armstrong provides the most complete published description of the harp along with comments on its history. His essential points are summarised here. He notes that the projecting portion of the box has an inscribed date of 1654 the figures of which he suggests ‘are certainly old, but it is impossible to say decidedly that they are of the period indicated’. He also notes as running up from the back of the harmonic curve firstly an incised carving of a right hand, the badge of O’Neill, above which is what he suggests was a rude representation of a ship upon the hull of which is a cross, beneath a heraldic wreath and other unintelligible marks. At the foremost upper end of the curve is a fish, probably a salmon, and on the upper portion of the front fore–pillar a small cross. He also notes that on the upper portion of the back of the box the initials EL have been ‘rudely incised’.

Armstrong notes that the harp had been painted more than once. On the right hand side of the box is painted a small male head and upon the left of the fore–pillar is painted ‘Edu.Lindse of Lennox, MDCCC4’. This painted name is then linked to the inscribed initials. When Armstrong moves on to discuss the harp’s history he then connects the name to a descriptive catalogue of an exhibition of antiquities which had been held to coincide with the British Association meeting held in Belfast in 1852. ‘To this collection a Mr E Lindsay of Belfast contributed three harps and in the descriptive catalogue page 44 it was described as ‘The Harp of O’Neill, one of the last of the old race of Irish Harpers, well known in Ulster about the end of last century’ and again in the Appendix, page 11, the following statement occurs; ‘Of the three Harps exhibited by Mr Lindsay, two of them are believed to have belonged to O’Neill and Hempson, men very remarkable in their day, and amongst the last of the genuine Irish Harpers’. Armstrong then suggests that the Mr E Lindsay who loaned the harp for the exhibition may have been the ‘Edu Lindse of Lennox’ whose name with the date 1804 is painted upon the harp, or possibly his son.[3]

In his next paragraph he states that it was not known how or when the harp arrived in the collections of the Belfast Museum but that while there it had been shown as the Harp of Carolan, however that when displayed at the Musical Loan Collection in Dublin in 1899, it was there exhibited as the Harp of O’Neill, the notice in the catalogue being copied from the earlier one of 1852. Armstrong also includes at this point a statement from the Ulster Journal of Archaeology for January 1901 that ‘it was the harp of Arthur O’Neill and had subsequent to the death of that noted harper, been in the possession of Mr. Edward Lindsay of Belfast who once gave a performance upon it at a meeting of the Anacreonic Society’. This is referenced to a footnote where he suggests that the fact that it was playable means that whoever had it before it became the property of the Lindsay family did not part with it on the account of it being worthless as a musical instrument. He also notes a tradition that a favourite harp of Arthur O’Neill was destroyed when the house of the O’Neills of Glenarb was burned and that this did not strengthen Mr Lindsay’s assertion.

In his conclusions Armstrong suggests that there could be no reasonable doubt that the harp was at one time in the possession of some person of the name of O’Neill, (presumably based on the carved hand of the O’Neill already noted), but Armstrong continues that

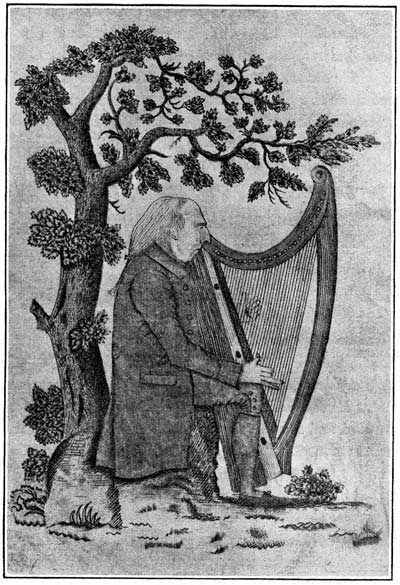

“there is no proof that the person was Arthur O’Neill, who in the two engraved portraits, probably from the same drawing, is represented as playing upon a totally different instrument. It is scarcely likely that the paragraph in the Appendix to the Descriptive Catalogue of 1852, viz, that it was believed to have belonged to O’Neill would have been printed if it had then been known to have been his harp. And the statement that it was acquired by Mr Edward Lindsay after O’Neill’s death is not likely to be correct as his death occurred in 1816 and the Harp appears to have been in the possession of a Mr Edu. Lindsay in 1804”.

Although Armstrong was quoting the article in the Ulster Journal of Archaeology regarding Edward Lindsay of Belfast and his performance on the harp, it is not totally clear if he had actually seen a copy of the journal as it is difficult to reconcile his conclusions with further information in that article concerning not just Mr Lindsay but also of the harp (of which he makes no mention). The article, Arthur O’Neill, the Irish Harper was one of a series by F. J. Bigger, who on referring to an engraving of O’Neill, a copy of which seems to have been given to each subscriber to that issue of the journal, remarks that the engraver, a Thomas Smyth of the Belfast engravers J. & T. Smyth, had supplied the additional information that:

“O’Neill’s harp is still preserved in the Belfast Museum and had subsequent to O’Neill’s death been in the possession of Edward Lindsay, the eccentric seedsman of Donegall Street, who once gave a performance upon it at one of the weekly meetings of the Anacreonic Society, held in their music hall, Arthur Street, he could play pretty well and was I think a member of the committee of the Harp Society.” [4]

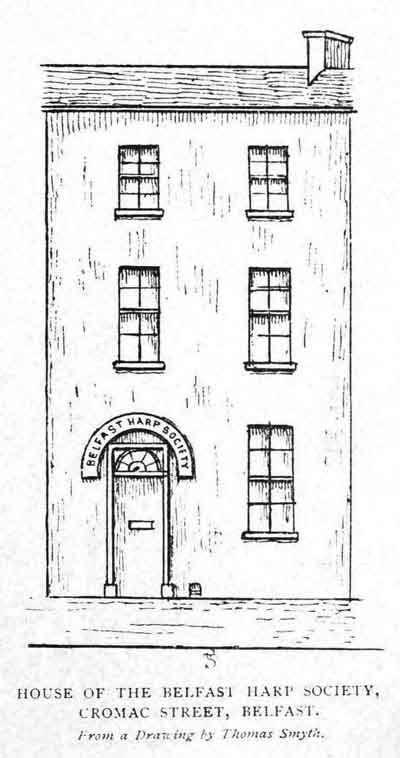

Engraving by Thomas Smyth, who lived in Cromac Street, next door to the Harp Society’s house pictured here.

The engraver Thomas Smyth had himself lived for sixteen years in Cromac Street, at first next door but one to the Harp Society’s house and afterwards directly opposite, and so had the full benefit of their practices. He was also responsible for a drawing and engraving of Valentine Rainey (tutor there from 1823 to 37), so if a very old man just might have known Arthur O’Neill, and was certainly close enough to O’Neill’s successors in the Harp School to be a well informed source which Armstrong would surely have mentioned had he known it. The information given by the engraver clearly identifies the harp’s owner at the time of the British Association meeting as one Edward Lindsay junior, who died in Belfast on the 13 December 1852, just a few months after the exhibition, and whose health at the time may have been responsible for the vagueness of the catalogue entry and who would certainly not have been in any position to subsequently correct any misunderstandings.

According to his burial record Edward junior was aged 52 at the time of his death and so was born around 1800[5] at Lilliput, at that time just outside of Belfast.[6] His father, Edward Lindsay senior, was a nurseryman and seed merchant, a fairly important profession at a time when agriculture still accounted for a large part of the economy. Edward senior had died in 1843 aged 84 and had been living at the time in Victoria Place, Belfast although described as formerly of Lennoxvale in Malone.[7] The father’s origins are a little vague, he was said to have come initially from Cork, although he had been in Summerhill, County Meath before moving to Belfast where he was firmly established in business at 4 Donegall Street by 1805.[8] His relict described as Amelia Lindsay died about two years after him, aged 80 and was according to the burial record born in Dromore.[9] There is reason to believe that her maiden name was Young as Edward junior in his will refers to ‘his grandfather Lennox Young, a doctor of medicine’ in county Down.

Apart from Edward junior, there were at least two other children: a sister, who was to survive him and a younger brother called Lennox Hamilton Lindsay who was to die, aged just 21 years old, in 1829 and whose forename following usual naming patterns confirms that Young was the maternal surname. It was an event which seems to have had a marked effect on the family demonstrated firstly by the death notice placed in the ‘Belfast News–Letter’ of the 25 August 1829 which ran well beyond the usual length of such entries and included two verses starting with the line ‘yes Lenox thou hast fled’. When in 1832 the remaining family moved from their home above and beside the seed shop in Donegall Street to a new dwelling built on land they were already using as nursery at Malone,[10] the new house and property there was named Lennoxvale, again in memory of the youngest son and an event which has a direct implications for both the date and meaning of the inscription on the museum harp referring to ‘Edu. Lindse of Lennox’ which despite the apparent date of 1804, must have been added after that move.

Having grown up in the house in Donegall Street, the young Edward Lindsay would have been brought up not far from the Harp Schools, both the original one run by Arthur O’Neill and the later one conducted initially by MacBride and then by Rainey. He would also have been a contemporary with many of the pupils of these schools and it is implied by a statement in a long obituary for him that whether formally or not, he seems to have had a close association with either the schools or their pupils;—

“for his favourite instrument was the Irish harp and his constructive skill enabled him, whilst yet a boy, to produce one of these sweet vehicles of sound, which, though rude in workmanship ‘discoursed most eloquent music’ beneath his fingers. In after life he made many finer harps on the true native model, and he was the possessor of one, lately exhibited in our museum, which is supposed to be an antique of some value.”[11]

Edward junior followed his father’s profession and seems to have taken over the family business around the time that Lennoxvale was built. Although having a less suitable temperament for that line of work than his father, he seems to have been a popular member of the community, being a supportive member of the Rosemary Street Presbyterian Church and on several occasions serving as a juror on the Belfast Quarter Sessions.[12] His interests were wide and he was to a degree eccentric although not as much as Armstrong, based on only one report, has suggested. Edward seems to have been a competent craftsman to the extent that he designed and oversaw the building of a commercial vessel, a schooner named Penelope which was launched and ready to receive cargo for Liverpool in February 1838.[13]

Expanding into shipping may have seemed to be a reasonable move as an extension of his own business as it is clear that he was regularly importing plants for his nursery, but he was beginning to over–reach himself. By 1843 he was clearly running into financial problems, which led to Lennoxvale, along with it’s eight acres of land and greenhouses, being put up for auction.[14] Edward seems to have continued on for while as a seedsman working purely from his shop in Waring Street, but clearly now in reduced circumstances. Despite his diminished financial standing, judging by his obituary, he was still regarded with fondness and there is nothing to suggest that his eccentricity made him unreliable as a witness or source.

It is an open question how far the descriptions of his harps in the 1852 catalogue quoted by Armstrong can be genuinely attributed to Edward, but we do have his own words on the subject recorded in his testament which should present a more reliable picture. Most of the will is concerned with providing for his sister Amelia, but in reference to the harps he says, ‘My Red Harp formerly O’Niels to the Belfast Museum’ and a little later ‘My Yellow Harp I leave to my sister’s daughter’. In other words, only two harps, one of which he does state had formerly belonged to ‘O’Neill’ with no claim by Edward of having harps connected with either Carolan or Hempson.[15] So is it possible that it was Arthur O’Neill that Edward Lindsay had in mind and what actually is known about Arthur O’Neill’s own instrument.

Arthur O’Neill, The Irish Harper” From an old engraving at Ardrigh”

as published with an accompanying article by F.J. Bigger (Ulster Journal of Archaeology, July 1906, Vol 12, p 100)

The two engraved portraits of Arthur (probably made from the same drawing, as Armstrong has suggested) certainly show a different instrument to the one currently in the Belfast Museum, and there was clearly also a tradition that ‘a favourite harp of Arthur O’Neill was burnt when the O’Neill house at Glenarb was burned down’. When Armstrong mentions this in a footnote he advances the tradition as further evidence that Edward Lindsay’s harp could not have been Arthur O’Neill’s, curiously ignoring the fact that the expression ‘a favourite harp of’ implies that the harper had more than one, and in any case if the tradition was true and O’Neill’s harp had been burnt then logically the harper would have needed a replacement.

However, the whole story regarding the instrument’s destruction by fire seems to be a conflation of two different events. The home of Arthur’s brother Ferdinand O’Neill at Glenart, (Glenarb), was burned down during the night of 7 July 1798 when a Lieutenant Hunter and his men of the Moy Company of Local Yeomanry raided it on the pretext of looking for arms. During the course of events, shots were fired, one of which struck Ferdinand’s wife and the roof was also fired to force those inside to come out. As a result of the death of Mrs O’Neill whose body was consumed by the fire, a Court Martial was subsequently held and although to a certain extent it was a whitewash, the records of those giving evidence do provide some believable information.

Among those said to have been in the house apart from Ferdinand and his family and servant was ‘a boy said to be the harpers son along with a harp the property of a blind man, O’Neill’s brother who made his livelihood by it’. According to the evidence most of the occupants escaped the fire through the back window and the harp was also retrieved the same way. Arthur O’Neill himself was not apparently present at the time, but as it would seem unlikely he would have gone anywhere without a harp this may be further evidence that he did in fact have more than one instrument.[16]

The next account of a harp belonging to Arthur which did get burnt comes from the notebook of John Bell and seems to have been related to him by Patrick Byrne, who should have been in a position to know;—

“Arthur O’Neill’s Harp was burned by Samuel Patrick (a bad harper) in the Harp Society house. That harp afterwards belonged to Rainy the harper. Patrick and others had taken umbrage at Rainie’s wife. It was burned as a bonfire, because Rainnies’s wife had gone out of the house. The brass [tuning] pins were pick’d out of Ranie’s harp & O’Neill’s and they sold them for drink.” [17]

H. G. Farmer, the editor of the notebook, goes on to note that one of the harps in the Belfast Museum ‘is, or was claimed to have belonged to Arthur O’Neill’ and also mentions the tradition that O’Neill’s favourite harp was destroyed when the house of Glenarb was burned, before concluding that if as Byrne had said a harp of O’Neill was burned in the Harp Society’s House, then it presumably occurred between 1823 and 1837 whilst Rainie was master of the Belfast Harp Society. The evidence clearly suggests that the story of the burning of a harp belonging to O’Neill really occurred after he had died and also probably accounts for the destruction of the instrument he is shown playing in his portrait. Therefore, if after his death any harps he owned were dispersed with one passing into the hands of Rainie, then assuming the Belfast Museum instrument had also belonged to him it would have been his second instrument, which in turn became the property of Edward Lindsay.

When examining the evidence for that harp having formerly belonged to Arthur O’Neill, the strongest case rests on both the appearance of the harp itself along with O’Neill’s own testimony. Armstrong’s case that due to the inscription by Edward Lindsay the harp must have been his on or prior to the date of 1804 no longer stands as the description ‘of Lenox’ can only be seen as a abbreviation for Lennoxvale, a name only appearing as a memorial to the brother who died in 1829. So the date of 1804 has to have been retrospective, possibly referring to the year that his father first obtained some land there for a nursery in an area which at that time was known as ‘the Course’.

The harp itself is generally considered to be an eighteenth century instrument which would also suggest that the date of 1654 carved into the projecting block is also retrospective and it is possible that it’s significance is in the date rather the harp. The year of 1654 was in the time of the Cromwellian land settlement when his former soldiers were granted lands cleared of their original Catholic owners. By that year it had become clear that the original lands set aside for the new settlers was insufficient and additional lands were made available especially in County Cork.[18] Given the suggestion that Edward Lindsay senior had originally come from Cork it is possible that 1654 was the date upon which the Lindsay family had first come to Ireland.

Finally, there is the question of the carvings on the top of the harmonic curve. The hand of O’Neill, (or possibly representing Ulster), is quite clear but the others less so. What Armstrong suggests was a ship under a heraldic wreath and some further incised marks is questionable as it does not in fact seem to be a ship. One very speculative interpretation, among others, is that they are an interlinked group representing parts of the arms of the four provinces and if that was what those carvings were meant to represent (and it is only a suggestion) then the only direct connection between someone with the name of O’Neill due to the ‘hand’ is removed.[19]

A view of the crudely carved underside of the harmonic curve on the Belfast Museum Harp.

(Photo ©2010 by Michael Billinge, used by permission.)

Another view of the neck of the Belfast Museum Harp.

(Photo ©2010 by Michael Billinge, used by permission.)

There is however, one further feature of this harp that seems not to have been commented on before which is that the right hand side of the harmonic curve near the point where it joins the top of the sound box has been very crudely carved away along it’s bottom edge. This in turn brings us to what Arthur O’Neill had to say about himself in his own words. O’Neill’s memoir was recorded around 1808 by Thomas Hughes, a lawyer’s clerk who was undertaking writing work for Edward Bunting. The memoir, especially those sections in which Arthur O’Neill mentions the lives of other harpers, was used by Sir Samuel Ferguson in the preparation of chapter five of Bunting’s 1840 collection. [20]

The original document is now among the Bunting papers but it has been edited and published twice, firstly by Mrs C. Milligan Fox and more recently by Donal O’Sullivan. In both cases there was some editing to tidy up the presentation but nothing that affects the section of relevance to this discourse. O’Neill not surprisingly can be shown to have erred in some parts of the memoir [21] and it is also clear that at least one major event, the death of his brother’s wife was not included. So when we have a major event directly affecting his own health and which is unlikely to be wrongly recorded, his memoir merits a closer examination and comment than it ever appears to have had before.

In the memoir of the period leading up to the 1792 Belfast Harp Festival, O’Neill recounts how during a visit to County Roscommon, he and his guide ‘got the most uncommon wetting I ever experienced ........ for I was shortly afterwards afflicted with such a severe rheumatism that I lost the power of my left–hand fingers’. He then continues that ‘In consequence of the affliction of the rheumatism I felt myself uncommonly unhappy in not being able to exercise my usual abilities on the harp and resolved to get home to Glenart as soon as possible’. On his way home he passed through Lough Sheelin and stopped at the home of Captain Somerville. The Captain, observing the harper’s disability, decided instead of having him play rather to read aloud to him from the Belfast News–Letter, wherein they found the advertisement inviting all the harpers to go to Belfast for the Festival.

O’Neill then moved on to Philip Reilly in County Cavan where he received a letter from Dr James MacDonnell specifically inviting him to attend Belfast on the 9th July to take part in the festival. Arthur was reluctant:

“In consequence of the rheumatism I felt my own incapacity and expressed it to my friend Phil Reilly, as I had not the use of the two principle fingers of my left hand, by which the treble on the Irish Harp is generally performed. Mr Reilly would take no excuse and swore vehemently that if I did not go freely he would tie me on a car and have me conducted to assist in performing what was required by the advertisement before–mentioned.”

When O’Neill reached Belfast, Dr MacDonnell decided ‘perceiving my bad state of health, thought it necessary to electrify me every day previous to the Belfast Ball’.[22]

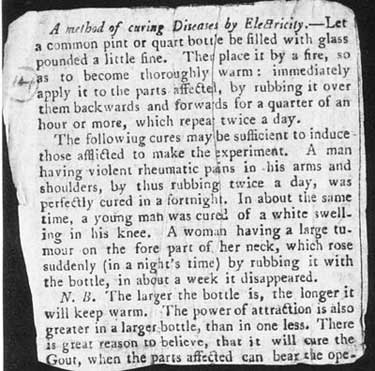

A contemporary newspaper cutting describing electricity as a treatment for disease. Please see footnote 23 for a transcription of this clipping.

The use of ‘electricity’ as a medical treatment had been tried on a number of ailments ever since its discovery had been made, usually with more optimism than a positive result. Its use as a treatment for rheumatism had been pioneered in Britain by the Rev John Wesley and so was a fairly new idea at that time. Dr MacDonnell having only qualified in 1784 was clearly like all young doctors open to any medical advances; however the efficacy of the treatment is doubtful and suggests that it was more a case of trying anything to improve Arthur O’Neill’s condition. Whether it worked is not clear but as the methods of ‘applying’ the static electricity usually involved rubbing and had the effect of warming the point of application that alone may have alleviated some of his symptoms.[23] Certainly after the Belfast Harp Festival Arthur was still having problems and according to his memoir went on to ‘Cushendall, where I remained two months for the benefit of the water at John Rowe Macdonnell’s’. This seems to have effected some improvement but rheumatism is a condition which, although its symptoms can vary from day to day, especially with changes in temperature, it does not improve with age and usually gets worse.

Arthur O’Neill seems to have struggled on playing for another twenty years or more so it would seem reasonable to suggest that at some point he was obliged to change hands to use the more impaired left hand for the bass and his less affected right hand for the treble. It is also plausible that rather have his life–long partner, his original harp, modified that a second harp was procured, the one now in the Belfast Museum, which has been associated with his name and which has the physical evidence of having been adapted with its harmonic curve severely cut back to make it easier for the right hand of a player, especially one who did not use nails, to access the top strings.

R. B. Armstrong’s original reservations about the Belfast Museum Harp centred mainly around three arguments. Firstly, that from the claimed connection to Arthur O’Neill in the 1852 exhibition catalogue onwards there was a lack of consistency in attribution. Secondly, that it would appear to have been in the hands of Edward Lindsay from 1804, well before Arthur O’Neill’s death, and finally that as Lindsay was known to have been eccentric, (a point that Armstrong makes even more emphatically in his manuscript notes),[24] Lindsay was therefore not to be regarded as a reliable source.

However, more extensive research has shown that there must be some doubt over how accurately the catalogue entry reflected the real views of a man within just a few months of his death, and are in any case at best a second–hand source. Edward Lindsay’s own words as reflected in his testament, made some considerable time before while he was fit and able, that his harp had been ‘O’Neill’s’ therefore must be regarded as the prime source. It is also clear that whatever the date of 1804 related to, it cannot have been added to the harp until after the house of Lennoxvale was built and so there is no actual evidence that the harp came into Lindsay’s hands before Arthur O’Neill died. Edward Lindsay was certainly eccentric but that does not make him unreliable and he seems to have been an intelligent man who was accepted with respect in his community. After all, in some ways R. B. Armstrong himself could be regarded as a little eccentric without it being a criticism of his own work.

The evidence in favour of the harp having been in the possession of Arthur O’Neill starts with Edward Lindsay’s testament in which he describes the harp as ‘formerly O’Neils’. Of course this does not necessarily have to have been Arthur O’Neill, but there is no other likely candidate. We have the testimony of Arthur’s own biography that he was having severe rheumatic problems with his left hand as early as 1792, as well as the evidence that the harp’s harmonic curve had been roughly carved out to make an over–large access for a right hand to play the treble.[25] All this is unlikely to be purely coincidental.[26]

When other more circumstantial evidence is also reconsidered against the probability that this harp was used by Arthur O’Neill, then it can also be shown to conform with this argument. For example, the fact that Arthur had left a harp at his brother’s house while he himself was away makes far more sense if he already had this second instrument with him, rather than the idea of a harper being separated from his harp. Likewise, the comment he makes in his biography when referring to his left hand and his reluctance to go the Belfast Festival, that it was the ‘hand the treble on the Irish harp is generally performed’, now looks like a self reference along the lines of ‘do as I say and not as I do.’ and may well have been an explanation to the biographer that the hand positions he was using at the time of the interview in 1808 were not the same as had previously been considered the normal playing position.

While the arguments presented here are primarily concerned with the question of whether there was a case for suggesting that the Belfast Museum Harp had previously belonged to Arthur O’Neill, they also raise a number of points that are really out side of the remit of that particular question. For example, if O'Neill was subject to serious impairment of his dexterity how did he manage to continue performing as a harper. One pointer to an answer is also mentioned in his memoir when referring to an occasion not long after the Belfast festival when he ran into Edward Bunting while on his way to Newry and spent some two weeks with him. As O’Neill puts it ‘He took some tunes from me, and one evening at his lodgings he played on the piano the tune of Speic Seoigheach, and I sung with him’.[27]

The fact that O’Neill only sung rather than played suggests that he may still have been having problems with his hands but also reminds us that Bunting’s large publication of just the music has tended to overshadow the fact that the harpers were primarily accompanying their singing and that although O’Neill’s rheumatic problems may have had a major impact on his purely instrumental ability, providing a harp accompaniment for his voice, (which would have been unaffected by the rheumatism), may have still been possible within his reduced dexterity.[28]

[1] Rimmer, Joan, The Irish Harp, (1977), 77

[2] Armstrong, R. B. The Irish and the Highland Harps, (1904), 88

[3] Armstrong, R. B. The Irish and the Highland Harps, (1904), 84–88

[4] Bigger, Francis Joseph, Arthur O’Neill the Irish Harper, Ulster Journal of Archaeology, Vol VII, No 1.(January 1901), 5

[5] Clifton Street Cemetery Records, 15 December 1852

[6] The Belfast News–Letter, 15 December 1852

[7] Clifton Street Cemetery Records, 2 September 1843

[8] Belfast Street Directories, 1805 through to 1808

[9] Clifton Street Cemetery Records, 10 October 1845

[10] The original nursery land seems to have been about 3 acres to which they added another 5 acres in 1830, see Public Record Office for Northern Ireland, (PRONI), D509/2512, the lease for which was renewed in 1842, PRONI, D509/2880. (There had been an earlier attempt to obtain ground for a nursery at Banbridge on Lord Devonshire’s estate,PRONI. D671/C/17), It was part of around 100 acres of land known as ‘the course’ formerly surrounded by a two mile long horse racing course belonging to the Countess of Donegal, now represented by Malone Road and Stranmillis Road. A house called Lennoxvale but built in the 1870’s still stands on the original property.

For development of the Malone part of the Donegall Estate see;– Carleton, Trevor, Aspects of Local History in Malone, Belfast, Ulster Journal of Archeology, 3rd series, vol 39, (1976), 62–67 and Malone, Belfast–The Early History of a Suburb, Ulster Journal of Archeology, 3rd series, vol 41, (1978), 94–101

[11] The Belfast News–Letter, 15 December 1852

[12] The Belfast News–Letter, 28 October 1834 and 27 October 1835, the Grand Jury on both occasions included Edward Lindsay junior.

[13] The Belfast News–Letter, 6 February 1838; Freeman’s Journal and Daily Commercial Advertiser 6 February 1838

[14] The Belfast News–Letter, 10 May 1843

To be sold by Auction, At Mr Hyndman’s Mart, Castle Place, Belfast on Friday the 2nd June, at the hour of One o’clock.

LENNOXVALE

The residence of E. Lindsay, jun, in the Parish of Malone, County of Antrim, about one mile from Belfast. The grounds are tastefully ornamented with Shrubbery and contain upwards of 8 Acres, Statute Measure, held for Lives, renewable for ever, under the Marquis of DONEGALL at the Yearly Rent of £6, 8s. 5d. The Dwelling house is commodious and there is on the Grounds a range of Glass, containing Peach, Vinery, and Green–house.

For particulars and information as to Title, apply to E & J. E. Garrett,Solicitors, 16 Castle–lane, Belfast, and 17 North Frederick Street, Dublin; or to the Proprieter, Lennoxvale or No 4, Waring Street Court, Belfast.

[15] Public Record Office of Northern Ireland, D1905/2/200

[16] O’Muiri, Reamon, A 1798 Court Martial with reference to Arthur O Neill, harper, Seanchas Ard Mhacha, vol 12, No 2, (1987), 138–148.

[17] Farmer, Henry George, Some Notes On The Irish Harp, Music and Letters, vol 24, (1943), 103

[18] Connolly, S. J. Divided Kingdom; Ireland 1630–1800, (2008), 109–117

[19] There is a stronger argument for the ‘ship’ to be a poorly carved crown, perhaps representing one of the crowns in the arms of Munster with above it the bent arm holding a sword, part of the arms of Connaught, leaving the instrument itself to represent the harp in the arms of Leinster which with the hand representing Ulster would in total complete the four provinces. The limited amount of space in which the ‘carver’ had to work would have made complete armorials impossible and other than the hand, what is there is really too crudely carved to be certain about any of it.

[20] O’Sullivan, Donal, Carolan; The Life Times and Music of an Irish Harper, ( 1958), volume 2, 143–144

[21] Donnelly, Sean, An Eighteenth Century Harp Medley, Ceol na hEireann — Irish Music, (1993), No1, 17–31

[22] O’Sullivan, Donal, Carolan; The Life Times and Music of an Irish Harper, (1958), volume 2, 173–174.

[23] Following is a transcription of the newspaper clipping which is represented above:

A method of curing Diseases by Electricity.— Let a common pint or quart bottle be filled with glass pounded a little fine. Then place it by a fire, so as to become thoroughly warm: immediately apply it to the parts affected, by rubbing it over them backwards and forwards for a quarter of an hour or more, which repeat twice a day.

The following cures may be sufficient to induce those afflicted to make the experiement. A man having violent rheumatic pains in his arms and shoulders, by thus rubbing twice a day, was perfectly cured in a fortnight. In about the same time, a young man was cured of a white swelling in his knee. A woman having a large tumour on the fore part of her neck, which rose suddently (in a night’s time) by rubbing it with the bottle, in about a week it disappeared.

N. B. The larger the bottle is, the longer it will keep warm. The power of attraction is also greater in a larger bottle, than in one less. There is great reason to believe, that it will cure the Gout, when the parts affected can bear the ope[ration].

[24] Armstrong Catalogue number 43, accessible via this Armstrong link

[25] The top section on many of the 18th century harps would have been quite playable with the right hand without any alteration to the structure. However, the Belfast/O’Neill Harp has a particularly steep string angle and a range extending high into the treble which gives it shorter top strings, and these combined factors reduce the space between the neck and box. Without this ‘modification’ the access for the right hand on this instrument would be severely restricted.

[26] In a letter from O’Neill to Lady Morgan, (Sidney Owenson), dating to probably circa 1806 and quoted by her in her book The Wild Irish Girl, (1806), p 117/8, he states, ‘My harp has thirty–six strings of four kinds of wire, increasing in strength from treble to bass: your method of tuning yours (by octaves and fifths), is perfectly correct; but a change of keys, or half tones, can only be effected by the tuning–hammer.’ While this clearly cannot be advanced as evidence for the Belfast instrument, which also has 36 strings, being O’Neill’s harp, it certainly does not conflict with that possibility.

[27] O’Sullivan, Donal, Carolan; The Life Times and Music of an Irish Harper, (1958). volume 2, 175.

[28] The fact that the failure to collect both the words as well as the music at the Belfast Harp Festival has led to a purely instrumental bias is just one aspect of a rather false picture of how the harpers actually performed in their normal lives. Sean Donnelly in his article, ‘The Famousest Man in The World for the Irish Harp’ published in the Dublin Historical Record, volume 57, No 1, ( Spring, 2004), pp 38–49, has noted the eclectic range of material used by the 18th century harper Murphy. He also points out, (page 46), the significance of Arthur O’Neill’s comment that the “harpers at the Belfast Harp Festival in 1792 ‘played all Irish music’, no doubt having been instructed to do so, which suggests that this was not always the practice”.

Submitted by Keith Sanger and Michael Billinge, 15 August, 2011.

Except where otherwise noted, content on this site is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available by contacting us at editor@wirestrungharp.com.