The two harps known as the ‘Queen Mary Harp’ and the ‘Lamont Harp’ have been closely associated with the Robertson family of Lude ever since they first came to public prominence following the report by John Gunn, commissioned by the Highland Society of Scotland in 1805. As two of the three earliest instruments associated with the medieval harpers of Scotland and Ireland they occupy an important place in the study of those musicians, but like the third example now known as the Trinity College Harp; from its location in Dublin, the firm details surrounding their early history are sketchy at best.

Even the details which are the basis of the names currently attached to the two harps which by tradition are linked to the early history of the ‘Lude’ family are only based on the account given by John Gunn, derived from now missing correspondence from the Robertson family. To examine those traditions against the Robertson family history therefore requires a detailed account of the family, its possessions and genealogy. This assumes an even greater importance when it is appreciated that while the surviving contemporary papers relating to Lude provide evidence for a number of harpers connected to that estate and the surrounding area, there is actually no specific mention of either harp before the Highland Society of Scotland arranged to bring them to Edinburgh and commissioned John Gunn’s report.

John Gunn’s report, albeit based on the covering correspondence from General Robertson, is the earliest surviving written evidence that refers to the instruments as the ‘Lamont’ and ‘Queen Mary’ Harps (a fuller discussion of Gunn’s account will be covered by the specific sections for each instrument). In this respect Gunn actually precedes the account by Donald MacIntosh describing his father hearing the harps being played by John Robertson of Lude sometime prior to Lude’s death circa 1730–31.

Donald MacIntosh was born in 1743, the son of James MacIntosh who had been the tenant of Orchilmore on the Urard Estate, just adjacent to that of Lude. Donald MacIntosh had published a collection of Gaelic Proverbs in 1785 and by 1801 had started working for the Highland Society of Scotland as translator and keeper of their Gaelic manuscripts. According to Donald in the account in which he describes the episode involving his father and Lude, Donald claimed that he was the person who drew the attention of the Highland Society to the harps at Lude which in turn led to the investigation.

However, Donald MacIntosh’s account was actually published posthumously by Alexander Campbell who edited the second edition of MacIntosh’s Proverbs in 1819 and had found the account among Donald’s papers.[1] The date this account was written can be fairly closely determined as Donald refers to Gunn’s report as having been published so would be after August 1807 and before Donald’s death in November1808. The original document seen by Alexander Campbell does not appear to have survived so we have no way of determining what editorial changes may have been made to Donald MacIntosh’s own words.

Returning to John Gunn’s report on the two harps undertaken for the Highland Society of Scotland there is a similar problem in that the original correspondence from General Robertson along with the other material which Gunn said was to be deposited with the Highland Society are not in their archives now. Indeed, the only information about the two harps currently held by the Highland Society archives are some references to the loan of the two harps from General Robertson for investigation and the engaging of John Gunn to undertake the study and make a report. These are noted in their Sederant Book covering the period from June 1803 to December 1808, while their current archive printed copy of that 1807 report was actually purchased by them in November 1937.

The missing material including an original copy of Gunn’s report which the Highland Society must have received was probably a casualty of the Edinburgh fire of 1824. The Society originally had an office in the Lawnmarket and although they had subsequently moved to Frederick Street in the New Town, they may still have held records at their original premises at the time of the fire. Neither is there any evidence regarding when and how the two harps were returned to General Robertson once the report had concluded. In fact the two harps once more to all intensive purposes vanish from the records until much later in the 19th century.

Although the Robertson family periodically stayed in Edinburgh, it must be assumed that the harps eventually found their way back to Lude; but after the death of General William Robertson in Edinburgh in January 1820, the estate had to be sold to cover the family debts. So the harps must have been moved elsewhere at that point. There was no mention of the harps in the Generals testament which was mainly concerned with the arrangements for the Generals brother, Colonel John Robertson to act as tutor to the Generals sixteen year old son, James Alexander.[2] In the event Colonel John Robertson died later that same year, but the harps had clearly had been inherited by the General’s son, Colonel James A. Robertson because at the next mention of them in May 1872 he was clearly the owner, although the two harps may at that point have already gone to Dalguise. This would partly explain a mix up in connection with a request for a loan for an exhibition.

A very aristocratic committee had been formed under the chairmanship of H.R. Highness The Duke of Edinburgh to organise a ‘Special Loan Exhibition of Ancient Musical Instruments’ to be opened in June 1872 at the South Kensington Museum, London. Someone, it would seem without Colonel Robertson’s knowledge, had agreed to loan the two harps. The first the Colonel heard of it was when he received a letter from His Royal Highness thanking him in advance for the loan. This resulted in a rather terse reply from Colonel Robertson stating that as he had ‘never been requested to lend any harps to the exhibition, he could not and never did express he was willing to do so’;[3] judging by the catalogue of the exhibition the two harps were not in fact loaned.[4]

The suggestion that the harps had already been moved to Dalguise is enhanced by Colonel James Robertson’s testament following his death in 1874. His address was given as 118 Princes Street, Edinburgh, (where he had been living since around 1857), and was described as ‘single’.[5] In the testament he leaves to ‘John Stewart Esq of Dalguise, now at the Cape of Good Hope, my gold watch and seals and to him I hereby confirm my former gift to him of my family charter chest & old papers, pictures and the two harps all which he well deserves from me’.[6]

The circumstances behind the ‘gift’ can be surmised. By the time his father died the young man had already lost his mother, Margaret Haldane, who died in 1805 shortly after giving birth to William his younger brother. William had also died young in 1813, so all he had left was his uncle who according to his fathers testament was to become the young mans guardian. However, his uncle died later in the same year as his father, thought possibly to have been a suicide following being obliged to move out of the ancestral home Lude House by the estates administrators.

This left the young man bereft of immediate family and income of any sort. So shortly afterwards he joined the army at the lowest commissioned rank of ensign, presumably having received somebody’s support to finance the purchase. This would not have been a career which provided any permanence of accommodation or allowing the carrying of a lot of personal effects with you. James Robertson and his friend John Steuart were of similar ages and backgrounds and had both lost fathers at around the same time, the main difference being that in the case of Dalguise, the estate was in a reasonable financial shape. So it does seem likely that those remaining family mementoes he had been allowed to keep were stored by his friend at Dalguise sometime before 1829 when John Steuart departed for South Africa.

Placing the two harps at Dalguise still leaves some questions over their exact location and who was nominally looking after them. John Steuart of Dalguise had inherited the estate at the death of his father in 1821, but from 1829 he was mainly non–resident in Scotland having been appointed High Sheriff of the Cape of Good Hope where he died in December 1881. The estate was for most of that time leased out and according to the adverts the house was described as ‘fully furnished’. The family of Beatrix Potter rented it between 1871 through to 1881 and at one point she noted in her diary being shown the ‘Queen Mary’ Harp in a cupboard at Stewartfield, a Dower–house built around 1822 for John Steuart’s mother. It seems likely that Stewartfield was retained for the Dalguise families own use and that the Lamont harp was also tucked away there.

The two harps were placed on display at a meeting of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland held on Monday 13 December 1880. The minutes describe them as ‘exhibited by John Steuart of Dalguise, through Charles D. Bell, F.S.A. Scot.’ and refer the readers to the subsequent paper by Mr Bell in that issue of the proceedings.[7] In his paper Mr Bell indicated that it had been agreed by Mr Steuart that the harps along with two Targes also from Dalguise, should be permanently loaned to the museum. Since John Steuart of Dalguise was still in the Cape of Good Hope at that time, (where he remained until his death), any negotiations must have been undertaken by letter but the two correspondents knew each other well. Before he retired back to Edinburgh in 1875 Charles Bell had been the Surveyor General of the Cape of Good Hope.

After the death of John Steuart the harps were left at the museum by their new owner, Mr C Durrant Steuart of Dalguise who presumably also gave permission for them to be loaned for the musical instruments section of the International Inventions Exhibition held in London in 1885.[8] According to one account the insurance to cover the two harps during the exhibition was £1500 for the ‘Queen Mary’ and £1000 for the ‘Lamont’.[9] If correct, these are remarkable sums when it is considered that only five years later when their owner Mr C D Steuart died the entire contents of Dalguise House were only valued at £918–2sh while his boats, a steam launch, a steam yacht and a houseboat only added another £360, a combined total apparently still below the insurance value place on just the ‘Queen Mary’ Harp alone. In that testament the ‘two old harps and highland targes in the antiquarian museum in Edinburgh’, were separately valued by Alexander Dowell the auctioneer and altogether they were assessed at an additional £105.[10]

The ownership of the instruments then passed to Mr J N D Steuart of Dalguise although the two harps along with the targes still remained on loan to the Society of Antiquaries Museum. Following the death of Mr Steuart in Lucknow, India on the 22 April 1903 his testament recorded in December of that year noted ‘Two old harps & two highland targes in the antiquarian museum per valuation by Alex Dowell, Edinburgh £300’.[11] At this point the whole of the Dalguise estate was put up for sale and the harps were among other items auctioned at Dowell’s Edinburgh Auction Rooms the following March. The Society of Antiquaries of Scotland had received a special, albeit onerous Government grant towards the purchase of both instruments. However the price paid for the ‘Queen Mary’ harp took most of the money and the ‘Lamont’ harp was sold to the agents for a private collector, Mr W. Moir Bryce, who subsequently left the harp to the Society when he died.

Not withstanding Gunn’s report published by the Highland Society of Scotland in 1807 and the far more reasoned review of the history behind the harps in the paper by Charles Bell published in the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland’s own Proceedings in 1880; the Society considered that ‘The price was unfortunately enhanced by the quite mythical attribution to Queen Mary’. While the exact connection between the harp and Queen Mary along with the association of the name Lamont with the other harp may be open to question, the lack of any references to them before Gunn’s enquiry and the association with the Robertson family of Lude, means that an exploration of the circumstantial case provided by the historical background to Lude and its owners may provide some answers.

What follows directly on from here is a general overview of the estate of Lude in Atholl along with the families who were associated with it during the time that the two harps were thought to have been around that area. For ease of reference there is in parallel with this section a tabulated ‘Tree’ which sets out the complicated ownership structure of the various families involved with Lude. For example, it is rarely appreciated that there was nobody using the description ‘Robertson of Lude’ at any point during the lifetime of Mary Queen of Scots. The following history of the family and Lude follows its general descent, while the more specific family connections to the ‘Queen Mary Harp’ and the ‘Lamont Harp’ are dealt with in the sections devoted to each instrument.

The family papers of the later Robertson’s of Lude traced their descent back to Patrick of Lude and then to his father Duncan of Atholl from whom they derived the Gaelic patronymic of Clann Donnchaidh. The later adoption of the surname or alias of ‘Robertson’ by the Lude family paradoxically comes from a different branch of the Clan, that of the Robertsons of Struan/Strowan since there was no ‘Robert’ in the Lude line as detailed in their family archives.

Following the death of Patrick of Lude, his son Donald would have ‘inherited’ Lude, but without any firm title as Patrick would have held Lude from his father, but by this time ‘Atholl’ had become a separate Earldom held by a different family altogether. So in 1447 Donald resigned Lude into the hands of King James II with the intention that they would be formerly granted back to him with a Crown Charter. Unfortunately, Donald died before that could be granted so the first Crown Charter was in fact granted in 1448 to his son John Donaldson and the heirs from his marriage with Margaret Drummond. This marriage produced two known children, the eldest son and heir called Donald Johnson of Lude and his younger brother usually referred to as ‘Charles of Clunes’.

At this point as we move firmly into the period covering the two harps the background becomes a little confused. Donald Johnson of Lude had a son called John Donaldson who inherited Lude from his father, but for reasons which are still far from clear in 1518 John Donaldson resigned Lude into the hands of James, Archbishop of St Andrews, chancellor and one of the regents of Scotland, in favour of Patrick Ogilvy of Inchmartin. This was followed by the issuing of a charter under the Great Seal firmly granting Lude to Patrick Ogilvy. Why this happened is a matter for speculation. In a comprehensive list of the various Lude papers drawn up probably by Colonel James Robertson as part of his own genealogical researches, at this point the note of the transaction simply has a gloss;— ‘here began the unfortunate claims of the Ogilvies on the barony of Lude’.

Unfortunate they may have been seen from the viewpoint of the now landless Colonel Robertson writing in the 19th century, but there is no doubt that the transfer of the Lude title to the Ogilvy’s of Inchmartin in 1518 followed the appropriate legal procedures of the time. The Lude family papers are fairly reticent about the event; the only other information being a suggestion in an early 19th century notebook of family ‘tales’ which claimed that Ogilvy of Inchmartin was the wicked uncle taking advantage of his nephew. Even if true, that does not explain the how or why and would have required a marriage at some point between the families of Lude and Inchmartin.

Although among the various draft family trees drawn up by William Robertson and his son James, one of them does have an ‘Ogilvy’ as wife to Donald Johnson, the logical point for such a marriage if the ‘uncle’ claim was correct; it is not repeated in any of the later more refined versions, probably because no evidence has yet been found from either family, the Robertsons or the Ogilvys, to support such a marriage connection. From this point any remaining members of the former Lude family would have become tenants of the Inchmartins who continued to hold Lude for several generations.

To return to the Robertson of Lude genealogy as claimed by General William Robertson and his family we need to go back to the ‘Charles of Clunes’ said to be the second son of John Donaldson and his wife Margaret Drummond and start by considering his name. The use of ‘Charles’ as an English or Lowland Scots equivalent for the man’s name is a late eighteenth and early nineteenth century introduction by the family. Although by the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries ‘Charles’ in that form was being used in the records for later Robertsons, (Charles Robertson of Achaleeks being one case[12]), in Scotland generally Charles as a forename only really appears after the reign of Charles I.[13] In the case of the branch of the family who initially took the patronymic of ‘Tarlachson’ it seems clear that the name of the man from whom they claimed descent was some form of the Gaelic ‘Tairdelbach’ whose modern form is still traced in Ireland as ‘Tarlach’.[14]

From Tirinie above Glen Fender looking towards Lude.

Photo ©2013 by www.WireStrungharp.com.

Therefore by implication the use of that patronymic is one piece of evidence that the ancestor who it was claimed married a daughter of Lamont thereby bringing the harp called by that name to Lude existed. (For the fuller exploration of that connection see the Lamont harp section via this link). Further firm evidence for his existence and parentage comes from an Instrument of Sasine for the 28th March 1474 among the Atholl papers at Castle Blair, where one of the witnesses is a ‘Carlet Johnson’.[15] The list of witnesses is headed by Alexander Robertson of ‘Strowane’ and ‘Carlet Johnson’ is the sixth name in the list, an appropriate place for a younger son of a cadet line. The forename cannot be anything else other than ‘Tarlach’ which together with the ‘Johnson’ links him firmly to John Donaldson and Margaret Drummond.

From Tirinie looking down to Bridge of Tilt with the woods around Blair Castle to the right

Photo ©2013 by www.WireStrungharp.com.

Tarlach Johnson was presumably dead by 1507 when his son John Tarlochson first appears among the Lude archives as a witness before in 1510 being granted a charter by John Donaldson of Lude of the lands of Easter Monzie. This was followed in 1513 by a similar charter for the lands of Wester Monzie which interestingly was signed at ‘Mekiclun’ [16] (Scots ‘MuckleClune’ or ‘Greater Clune’ probably equating with the Gaelic form of Cluniemor). This is perhaps the first hard evidence that John Tarlochsons’s father had held the lands of Cluny. One of the witnesses to the charter was a Findlay McEwin, possibly one of the family of harpers associated with the background to the Lamont Harp.

Following the transfer of Lude into the hands of Patrick Ogilvy in 1518 the Tarlochsons continued in possession of Easter and Wester Monzie although the two parts seem to have been combined into one as John Tarlochson’s son, also a John was described as ‘John Tarlochson of Monzie’, at least until after marrying Beatrix Gardyne and their acquisition of Inchmagranichan in 1564 when that became his ‘title’ although he continued to hold the tenancy of Monzies from Inchmartin. Before Lude was resigned to the Ogilvys, Monzie seems to have been the part of the estate where its owners resided. Probably in the part known as Wester Monzie as that was closer to Little Lude and the original Church of Lude.

The fact that the Tarlochson’s became tenants of both parts of ‘Monzie’ suggests that the new Ogilvy owners of Lude did not in fact take up residence there. There is some evidence to suggest that the Tarlochson’s acted as the Ogilvy’s Baillies for managing the estate and only rarely did the Ogilvys use the Lude designation instead of Inchmartine, and only then as in the case of a charter of sale by Patrick Ogilvy of Lude of ‘Owrwartmoir in the barony of Luyd’ where it specifically related to the management the Lude estate.[17] When several generations later in 1619 the then Patrick Ogilvy of Inchmartine decided to sell Lude, most of the lands in Lude, seem to have been wadset to members of the Tarlochson Family.[18]

When in 1619 Lude was disponed, (sold) by Inchmartine to Colin Campbell younger of Glenorchy for £10460 –13sh – 4d, the right to reversion of the wadsets was also transferred to Glenorchy. It seems probable that there was some degree of collusion involved as Colin Campbell’s sister was the mother of Inchmartine and the acquisition was probably a move by the Campbells of Glenorchy to extend their estate eastwards. However, in 1621 they sold the actual lands of Lude to Alexander Robertson of Inchmagranichan, (who was the grandson of John Tarlochson and Beatrix Gardyne), for 16750 merks, (£11166–13sh–4), but kept the superiority. Then in 1624 Glenorchy sold the superiority of Lude to William Murray, Earl of Tullibardine for a further 1325 merks. When the Atholl and Tullibardine families became one, this meant that the boundaries of the Lude estate now marched with those of Atholl, their feudal superior.

Initially there seem to have been few problems. Alexander Robertson dropped using the style ‘of Inchmagranichan’ and adopted that of ‘Robertson of Lude’ while setting about adapting to his new status. Rather than returning to the old centre of the Lude Estate at Monzies, which in any case would have meant removing his own relatives, he established a new home at Balnagrew.[19] The new home was on a six merkland he already held from the Laird of Inchmartine and was lower down and closer to the river than Monzie; while his neighbours home at Blair Castle was probably less obvious.

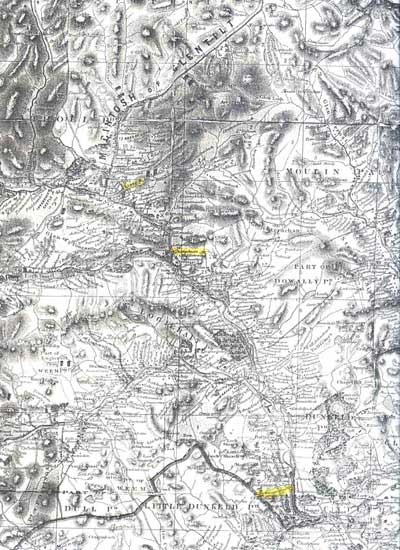

Part of Map from Comitatus de Atholia: the earldom of Atholl by James A. Robertson, (1860), showing relative positions of Inchmagrannoch and Lude. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

You may click on the above image to load a high resolution image file.

The change from being a tenant to landed proprietor also required setting up his own administration and the first evidence for that process was the organisation of regular Lude Barony Courts. These commenced in March 1622 at Balnagrew and the appointed Baillie was Alexander Stewart of Bonskied, who was married to Lude’s sister Margaret Robertson; a talented lady who around 1630 compiled a very large collection of mostly Scots poetry. It was around this period that the family adopted the nearby church of Kilmaveonaig as their burial place while the church at Lude was allowed to fall into disrepair. The dates on the memorials at Kilmaveonaig commence after 1621 and the purchase of Lude by Alexander Robertson with the earliest name, his mother, Agnes Gordon who died in 1634, but not his father who had died in 1615.

The Tarlochsons or Robertsons, as they henceforth called themselves had reached a high point. They now owned Lude as well as still holding Inchmagranichan, but the fact that they did not actually have the Feudal superiority of Lude was to develop into a bone of contention with associated legal costs which the Lude family stubbornly continued to incur. It was Alexander Robertson who seems to have initiated the dispute when in 1629 he tried to stop John Earl of Atholl being served heir to his father William Earl of Tullibardine because the superiority of Lude was part of the inheritance. Because the Feudal title for Lude had been legally acquired by Tullibardine the action failed, but was certainly not the best way for Alexander Robertson to endear himself to his very close neighbour and whether he liked it or not, his feudal superior.

As the two estates shared many boundaries in an age when maps, let alone accurate ones were non existent the potential for disputes regarding marches was always present even among cooperative proprietors. However, Alexander and his descendents seemed to antagonise their larger neighbour more than was common to the extent that in 1679 the then Earl of Atholl retaliated by refusing, as the feudal superior to give a charter for Lude to the young heir John Robertson. Atholl eventually complied after more legal actions but the costs of the continued squabbles were a drain on the Lude finances as shown by the loss of Inchmagranichan in 1697. Alexander Robertson of Faskally had married Ludes daughter and Lude being short of money had used Inchmagranichan as surety for the agreed sum of the dowry. When by 1697 the money was still not forthcoming Faskally sold Inchmagranichan to Atholl and so added another reason for the Lude family to feel aggrieved.[20]

The uneasy relationship between the two estates continued through the next century with periods of some cooperation punctuated with legal actions, usually initiated from the Lude side. Despite the lack of success and drain of money in legal costs the fact that Atholl held the feudal superiority continued to be an irritant; in 1794 James Robertson of Lude and again in 1804 his son General Robertson attempted to persuade the Duke of Atholl to sell them the superiority of Lude. Since in both cases the Lude estate was financially in dire straits the offers, which were declined, were for an exchange of some land in return for the feudal title.

True to previous form within a few years General Robertson was again embroiled in legal actions against Atholl in which he was unsuccessful, despite in 1815 appealing the decision of the Court of Session in Edinburgh right up to the House of Lords in London. The costs proved to be the final financial straw and shortly afterwards rumours started to circulate that the Lude estate was to be placed into administration although in fact that did not actually happen until the death of General Robertson in 1820.

This almost single minded obsession with obtaining the feudal title to Lude irrespective of the costs which seems to have driven the descendents of the ‘Tarlochson’ also coloured their approach to their own family history. From the earliest signs of the family’s attempts at sketching out their family tree it is clear that the members of the family prior to the Alexander Tarlochson/Robertson who bought Lude in 1621 were simply treated as necessary steps in tracing a line back to Patrick of Lude and his father Duncan of Atholl. It is as if they had to be there to make that connection, but otherwise they were of little interest because they were a reminder that during that period Lude was in fact held by others.

Indeed simply going by the family trees made by General Robertson and his son James without placing them in context with the rest of the Lude records it is quite easy to miss the fact that there was not one single continuous family called Robertson holding Lude down through the years without any interruption. This is probably the major factor behind the lack among the family papers of any written historical lore about Beatrix Gardyne and the QM harp or that her granddaughter, Margaret Tarlochson[21] had compiled one of the largest collections of contemporary Scots verse in 1630.[22] This in turn opens another window in the history of the Lude harps which are usually set against a Gaelic cultural background. The Scots verse in that collection would have been sung and with the close connections of the harps, the contemporary harpers and that family, then it is likely that the two harps were also utilized in the performance of Lowland Scots verse.

[1] A copy of MacIntosh’ Proverbs is available to view here, courtesy of the Library of Congress

[2] James Alexander Robertson was born on the 28 June 1803.

[3] NAS GD244/4/1/3/9/2/1–4

[4] Some Acount of the Special Exhibition of Ancient Musical Instruments in the South Kensington Museum, Anno 1872. Appendix No. 2, in Engle, Carl, A Descriptive Catalogue of the Musical Instruments in the South Kensington Museum. (1874), p 367; The harps which were exhibited included the Kildare, Dalway and the one owned by Archdeacon Saurin, subsequently to be added to the museums own collection.

[5] Statutory Deaths 685/02 0504.

[6] National Archives of Scotland, SC70/4/152/594–595

[7] Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, vol XV, (1880–81) Minutes and Notice.

[8] The Times, Monday 4 May 1885; The Graphic, 5 Sept 1885.

[9] Hipkins, A. J, Musical Instruments Historic, Rare and Unique, (1888), 5; This work manages to add to the historical confusion by making General Robertson the last performer on the harps rather than the General’s great grandfather, but this work was even more controversial in regard to its author and the background to its publication. For a discussion of that background see the review of the reprint by Arnold Myers in The Galpin Society Journal, vol. 41 (October 1988) pp. 118–120, and the prospectus from 1884 by Mr Robert Glen include in his privately printed and circulated ‘Copy Correspondence as to the publication of Book on ‘Ancient Musical Instruments And Plates of the said Instruments’ published in 1887.

[10] National Archives of Scotland, SC49/31/144/125–126. Charles Horace Durrant Steuart of Dalguise died on the 29 December 1890.

[11] National Archives of Scotland, SC49/31/194/556 item 9

[12] The form ‘Charles’ seems to have evolved from the use of a Latin equivalent for ‘Tarlach’ which also appears have come down through the Strowan cadet line of Fascally. A seal of ‘Charles of Fascally’ on a document dated at Dunkeld in October 1543 reads ֹS Caroli Roberti’. Scottish Heraldic Seals, by J.H Stevenson and M. Wood (1940), p 563

[13] Black, G.F, The Surnames of Scotland. (1946), 147.

[14] O’Corrain, Donnachadh and Maguire, Fidelma, Gaelic Personal Names, (1981), p 169.

[15] Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts, 7th Report part 2, Atholl papers, p 709. number 59

[16] National Archives of Scotland GD132/10–11–12

[17] Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts, 7th report, part 2, Atholl papers, p 712, number 89 and 715 number 120.

[18] National Archives of Scotland, GD132/772. Wadset is a Scottish legal term used when lands are pledged by their owner to a creditor, often the actual tenant, in return for a loan. Usually in the form of a mutual contract whereby one party sells the land and the other grants the right of reversion. Before banks, actual cash money in Scotland was in short supply and wadsets were frequently used by land owners either to raise hard cash or as pledges that a money payment would be made later.

[19] Subsequently renamed ‘Lude House’ by the McInroys who bought the estate following General Robertson’s death in 1820 and were responsible for building the current 19th century house.

[20] Chronicles of the Atholl and Tullibardine Families, vol 1, p 602.

[21] It is possible that Margaret may have been buried in the Lude vault in the church at Kilmaveonaig. It would certainly explain why the Stewarts of Bonskeid had a seat allocation in that church. Her volume of Scots and English verse is manuscript MS15937 in the National Library of Scotland. It has also been transcribed as part of his theses by S J Verweij which is available online at www.theses.gla.ac.uk/329/

[22] For a recent discussion of the manuscript and its contents, Verweij, Sebastiaan Johan. The inlegebill scibling of my imprompt pen’, the production and circulation of literary manuscripts in Jacobean Scotland c1580–c1630. Thesis, University of Glasgow, (2008).

Submitted by Keith Sanger, 7 June, 2013.

Except where otherwise noted, content on this site is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available by contacting us at editor@wirestrungharp.com.